"MATERIA Y VIBRACIÓN, 1956 - 1974"

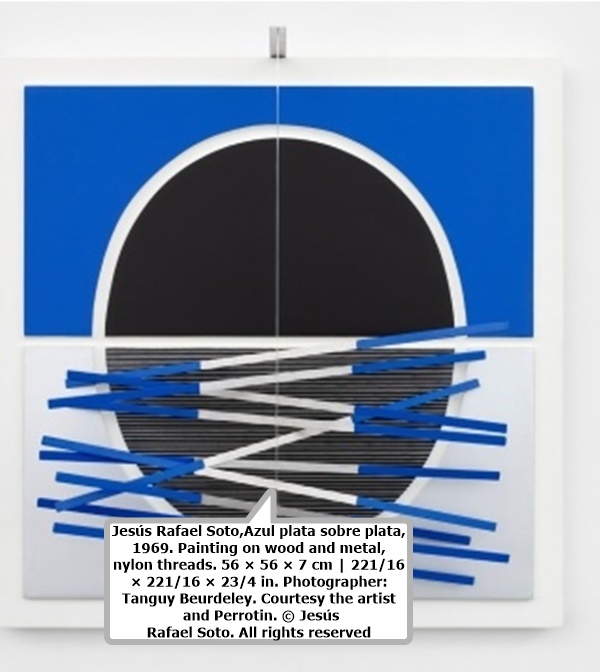

Jesús Rafael Soto

PERROTIN

130 ORCHARD STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10002TEL : +12128122902 e-mail:

Multiple location : Shanghai New York Paris(3) Hong Kong Tokyo Seoul

March 5 > April 16, 2022

Perrotin is pleased to present an exhibition of historic works by the

late pioneer of Kinetic art, Jesús Rafael Soto. Opening on March 5 in

New York, Perrotin will present a survey of works from 1956–1974,

when Soto was at the heart of the art scene both in Europe and the

Americas, and leading up to his groundbreaking Penetrables series.

The following essay is an excerpt from Soto’s Multidimensionality:

From Dematerialization to Relationality, written by curator Jesús

Fuenmayor for a catalogue published alongside Materia y Vibración,

1956 - 1974

… Times change, and notions of time and space change with them. In the notion of space-time we experience today, we speak not only of the fourth dimension, but also of multidimensionality—that is the legacy we will leave the future.

— Jesús Soto1

In some experimental contemporary art practices, a path can be traced from the dematerialization of the 1960s to the relationality, or “relational aesthetics,” of the turn of the twenty-first century. Following that path both illustrates the centrality of kinetic artist Jesús Rafael Soto’s work to the international art scene and attests to its currentness as it has regained the historical weight it is due.

On the basis of the works exhibited here—works produced by Soto during the years he was at the heart of the art scene in Europe and in the Americas (1956–1974)—that path between the term dematerialization and the term relationality offers, in my view, a way for us to begin to grapple with why we need not only to revisit Soto’s work today, but also to do so moving forward. In this brief introduction, I will provide a concise overview of how those terms developed and their intersections with Soto’s work in order to better understand some of his most important achievements.

Each term has its specific history. Dematerialization is generally used to refer to the intangible aspects of a work of art or materiality’s (relative) loss of importance to it. The term always operates on a symbolic level: absolute dematerialization is impossible. Although in the United States, the point of reference for dematerialization as understood in contemporary art is Lucy Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, published in 1973, the term was widely used as early as the 1960s. One striking example is the text “After Pop, We Dematerialize” written by Argentine artist Oscar Masotta in 1967, the same year that some eminent critics, among them Frank Popper and Jean Clay, used it in relation to Soto’s work.2 Already in the 1950s, Yves Klein used dematerialization to explain his work, The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility, “The Void.” And, of course, Lászlo Moholy-Nagy—a major influence on Soto—envisioned a future of ever greater dematerialization.3 Though he sometimes employed the term immateriality instead of dematerialization, Soto himself used it in interviews, texts, and even in titles to shows, including the 2005 retrospective held at the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro: Soto – A Construção da Immaterialidade.4 What matters here is that, from his first experiments with vibration, Soto’s aim was “the methodical destruction of all stable form, the molecular fragmentation of solids, the dilution of volumes.”5

The concept of relationality in art produced at the turn of this century was developed by Nicolas Bourriaud in his book Relational Aesthetics, published in French in 1998 and in English in 2002. The concept has been seen as a means to underscore the importance of viewer participation in the works of certain artists associated with the second avant-gardes, among them those, like kinetic artists, interested in bringing movement into their work. Art historian and critic Claire Bishop, who has studied the participative in art extensively, holds that the art that meets Bourriaud’s definition of relational aesthetics is “open-ended, interactive, and resistant to closure, often appearing to be ‘work-in-progress’ rather than a completed object.”6 There is unquestionably an affinity between that definition and the concept of the open work introduced by Umberto Eco on the basis of his readings of kinetic art7. As he explains in his book, Bourriaud seeks to politicize that definition, claiming that relational artists operate in “the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than the assertion of an independent and private symbolic space.”8 Bourriaud’s analysis is like Guy Debord’s critique of kinetic artists;9 to the latter, Soto replied that the political uprising of the time, in reference to May 1968, “did not represent anything decisive for my work because, like others, I had been toying for some time with the idea of taking my art into the street, of making it more popular.10

Soto’s formula was nearly infallible: first, destroy form and, with it, composition by means of seriality; next, dematerialize the art object and turn it into vibration; finally, leave viewers open space in which to reinvent themselves. Of course, that formula can only be postulated in retrospect; the artist had to spend many years experimenting, facing challenges regarding both what he had already done and where he was going, before he was able to articulate what now seems like the impeccable, indeed almost mathematical, development of an art that was at the forefront of the avant-garde in Europe for a full two decades. To look at Soto through the lens of our times, I wanted to begin with a description of what was at play in those first works in which he was able to create the “illusion” of shattering form through analysis and dissection of perception. Consider how today Alexander Alberro describes Espiral, one of Soto’s fundamental works from that time: Materiality and immateriality are in tension, but in a purely visual manner. Soto has no evident interest in the inherent physical properties of the materials. Moreover, the fragile and dematerialized optical effects that challenge the eye’s power to control what it sees intensify and decrease depending on the spectator’s position. As the spectator ambulates laterally across the work, the lines of the spirals seen against the luminous white ground join and separate, and the two layers alternately contract and expand. The incessant rippling effect of this work differs significantly from the optical effects obtained by the mere repetition of elements on a flat surface in Soto’s art of the previous two or three years..11

That work ushered in a series to which Soto’s interest in dematerialization and relationality would be central. In the words of the always-eloquent artist:

I am not interested in the connections between things, only in their relationships. I am not interested in how colors or lines are connected. Relationships are worth more than connections. ... My work is essentially relationship. Not between two elements of the work itself, but between the principle that governs the work—for instance, dematerialization—and a general law of the universe that determines everything.12

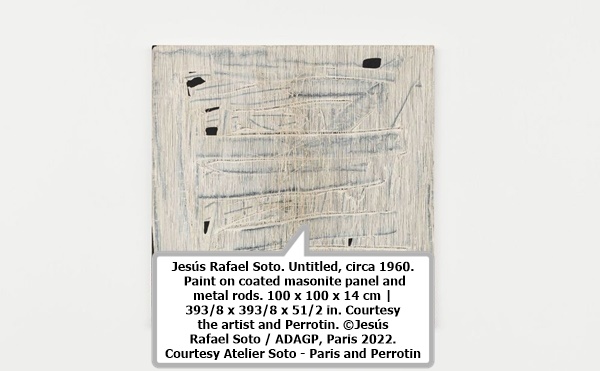

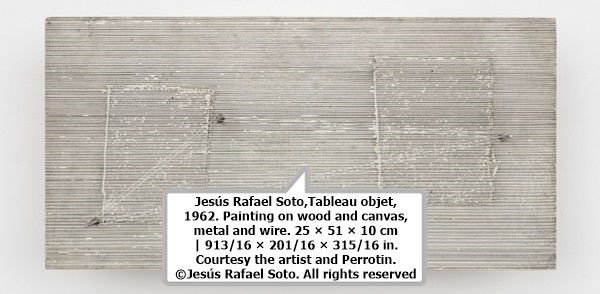

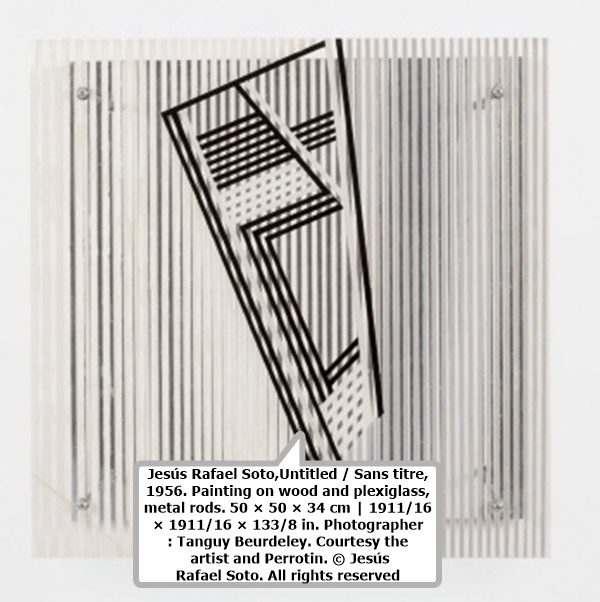

This was one of the most ambitious programs of the period. It encompassed “fundamental concepts like fugacity, dematerialization, instability, the invisible, the environment, permutation, undulation, ubiquity and randomness”13 concepts paradigmatic to Soto’s research as a whole and reflected in a work from 1956 featured in this exhibition, a work from the series called Estructuras Cinéticas de Elementos Geométricos. Produced after his first kinetic structures from the late 1950s, the Vibraciones series is unquestionably a milestone in Soto’s research. No piece could better represent it than Vibración pura, a work from 1960 featured in this exhibition. In this work, the feverish activity of the extremely irregular support in the background becomes something like a camouflage for the twisted metal rods suspended in front of it. In the unique vibration produced, the rods seem to emerge from the support, as if they had been dug out of it, rather than floating in front of it. Soto spoke of these pieces in terms different from the culmination connotations used by legions of his followers and experts in his work. It is perhaps because of their greater affinity with works by major figures in the French New Realism and the Informalist movements, led by artists very close to Soto (Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely, and Lucio Fontana, among others), that this series of early vibrations has been particularly coveted by collectors and museums alike. In an interview with the most important art magazine of the time in the country of his birth, Soto spoke of those artists, also known as Neorealists: The destruction of form imposed by the Informalists was of great interest to me, in a way, but I realized that what they were proposing was the destruction of form as a solid body, by liquefying it. I, on the other hand, was attempting to destroy matter in order to transform it into energy. I did not wish to extol natural elements like branches, or nets and ropes, but to prove that their matter could be transformed into energy. Energy not in the scientific sense, but as I conceived it: a state of sensibility.14

Soto thus distanced himself from these artists and explained that his concerns differed from those of the Informalists. Throughout his career, Soto was able to put into practice this idea of the transformation of matter into energy thanks, fundamentally, to the groundbreaking discovery of vibration that makes his work unmistakable. Vibration was his identifying stamp to such an extent that Soto himself considered this phase a singular period in all his work. “All I cared about [at that time],” Soto said, “was to show to myself that my idea did not depend on a certain way of doing things. ... I felt the need to prove to myself that I could make use of anything at all in my work. The idea was to incorporate things very mundane but also highly formal (scraps of wood, pieces of wire, needles, bars, and tubes), to disintegrate them entirely through pure vibration.”15 In short, his mastery, his virtuosity was such, by this phase, that he could make anything vibrate.

The dematerialization of the object and the relativization of perception are among the radical advances embraced by the contemporary art agenda to which Soto left an invaluable legacy. He unquestionably contributed to the constant reinvention and transformation of accepted notions of how to experience a work of art, an enormous challenge to the different visions of the world and our relationships with what’s most entrenched in that world. Perhaps it is best, in closing, to put it as the artist did: “The immaterial is the sensible reality of the universe. Art is the sensible knowledge of the immaterial. Becoming aware of the immaterial at the state of pure structure is to make the final step towards the absolute.

Venezuelan-born artist Jesús Rafael Soto trained at an art school in Caracas. In 1950 he moved to Paris, which remained his base until his death in 2005. In 1955 Soto participated in Le Mouvement (The Movement) at Galerie Denise René, the exhibition that effectively launched kinetic art. During the same decade, he began making linear, kinetic constructions using industrial and synthetic materials such as nylon, Perspex, steel, and industrial paint. Major exhibitions of Soto’s work have taken place at Signals London (1965); the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (1971); the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1974); and Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris (1979).

1 Rafael Pereira and Jesús Soto, “La experiencia del viejo matador: entrevista a Jesús Soto por Rafael Pereira,” Kalathos, no. 4 (October–November 2000).

2 In this article, Masotta makes reference to El Lissitsky’s 1926 essay “The Future of the Book,” which uses the term dematerialization as we do today. See Oscar Masotta, “After Pop, We Dematerialize,” in Listen, Here, Now! Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, ed. Inés Katzenstein (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2004), p. 216. See as well Frank Popper, Introduction to Lumière et Mouvement (exh. cat. Paris: Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1967) and Jean Clay, “Le cinétisme est-il un académisme ?” Robho, no. 2 (November–December 1967).

3 According to Antonio Somaini, “This idea [that light is the fundamental artistic ‘medium’] led Moholy-Nagy to formu- late the thesis according to which all art forms—painting, sculpture, photography, cinema, design, stage design or archi- tecture—develop according to a teleologically oriented tendency that leads from stasis to motion, from opaqueness to transparency, and from different concrete materials towards a state of progressive dematerialization.”“The Surface Becomes a Part of the Atmosphere”: Light as Medium in László Moholy-Nagy’s Aesthetics of Dematerialization,” Screen 61, issue 2 (Summer 2020): p. 289

4 “Everything will be painted white to receive the pictorial climate of the sensibility of dematerialized blue” (my empha- sis). Excerpt from “Preparation and Presentation of the Exhibition on April 28, 1958 at the Iris Clert Gallery, 3 rue des Beaux-Arts, Paris,” in Overcoming the Problematics of Art: The Writings of Yves Klein, trans. Klaus Ottmann (Thompson, CT: Spring Publications, 2007), p. 47. Soto speaks of immateriality in Soto (exh. cat. Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1969), and of dematerialization in “Statements by Kinetic Artists,”

Studio International 173, no. 886 (February 1967): p. 60. 5 Jean Clay, “Soto, de l’art optique à l’art cinétique,” Soto (exh. cat. Paris: Galerie Denise René, 1967), quoted in Arnauld Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, trans. Martin Back and Thierry Noujaim (exh. cat. Perrotin: Paris, 2014), p. 156.

6 Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Fall 2004): p. 52.

7 Ibid., p. 62.

8 Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002), p. 14.

9 See Mónica Amor, “La beauté est dans la rue ! Jesús Rafael Soto’s 1969 Public and Exceptional Foray,” in Soto. The Fourth Dimension (exh. cat. Bilbao: Guggenheim Museum, 2020), pp. 39–43.

10 Soto, quoted by Miyó Vestrini in “Jesús Soto: Venezuela es Uno de los Raros Paises de America Latina Donde Existe la Necesidad de Crear un Arte Nuevo,” El Nacional, July 24, 1971, p. 8, quoted in Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, p. 166.

11 Alexander Alberro, Abstraction in Reverse: The Reconfigured Spectator in Mid-Twentieth-Century Latin American Art (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), p. 118.

12 Soto, “Statements by Kinetic Artists,” p. 60.

13 Clay, “Le cinétisme est-il un académisme ?” quoted in Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, p. 165.

14 Soto, interview with Iván González, “Soto: liberar el material hasta que se vuelva tan libre como la música,” Imagen, no. 32 (September 1–15, 1968), p. 10, quoted in Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, p. 159.

15 Ariel Jiménez, Conversaciones con Jesús Soto (Caracas: Fundación Cisneros, 2001), p. 62.

16 Soto in Soto, 1969, p. 56, quoted in Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, p. 166.

… Times change, and notions of time and space change with them. In the notion of space-time we experience today, we speak not only of the fourth dimension, but also of multidimensionality—that is the legacy we will leave the future.

— Jesús Soto1

In some experimental contemporary art practices, a path can be traced from the dematerialization of the 1960s to the relationality, or “relational aesthetics,” of the turn of the twenty-first century. Following that path both illustrates the centrality of kinetic artist Jesús Rafael Soto’s work to the international art scene and attests to its currentness as it has regained the historical weight it is due.

On the basis of the works exhibited here—works produced by Soto during the years he was at the heart of the art scene in Europe and in the Americas (1956–1974)—that path between the term dematerialization and the term relationality offers, in my view, a way for us to begin to grapple with why we need not only to revisit Soto’s work today, but also to do so moving forward. In this brief introduction, I will provide a concise overview of how those terms developed and their intersections with Soto’s work in order to better understand some of his most important achievements.

Each term has its specific history. Dematerialization is generally used to refer to the intangible aspects of a work of art or materiality’s (relative) loss of importance to it. The term always operates on a symbolic level: absolute dematerialization is impossible. Although in the United States, the point of reference for dematerialization as understood in contemporary art is Lucy Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, published in 1973, the term was widely used as early as the 1960s. One striking example is the text “After Pop, We Dematerialize” written by Argentine artist Oscar Masotta in 1967, the same year that some eminent critics, among them Frank Popper and Jean Clay, used it in relation to Soto’s work.2 Already in the 1950s, Yves Klein used dematerialization to explain his work, The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility, “The Void.” And, of course, Lászlo Moholy-Nagy—a major influence on Soto—envisioned a future of ever greater dematerialization.3 Though he sometimes employed the term immateriality instead of dematerialization, Soto himself used it in interviews, texts, and even in titles to shows, including the 2005 retrospective held at the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro: Soto – A Construção da Immaterialidade.4 What matters here is that, from his first experiments with vibration, Soto’s aim was “the methodical destruction of all stable form, the molecular fragmentation of solids, the dilution of volumes.”5

The concept of relationality in art produced at the turn of this century was developed by Nicolas Bourriaud in his book Relational Aesthetics, published in French in 1998 and in English in 2002. The concept has been seen as a means to underscore the importance of viewer participation in the works of certain artists associated with the second avant-gardes, among them those, like kinetic artists, interested in bringing movement into their work. Art historian and critic Claire Bishop, who has studied the participative in art extensively, holds that the art that meets Bourriaud’s definition of relational aesthetics is “open-ended, interactive, and resistant to closure, often appearing to be ‘work-in-progress’ rather than a completed object.”6 There is unquestionably an affinity between that definition and the concept of the open work introduced by Umberto Eco on the basis of his readings of kinetic art7. As he explains in his book, Bourriaud seeks to politicize that definition, claiming that relational artists operate in “the realm of human interactions and its social context, rather than the assertion of an independent and private symbolic space.”8 Bourriaud’s analysis is like Guy Debord’s critique of kinetic artists;9 to the latter, Soto replied that the political uprising of the time, in reference to May 1968, “did not represent anything decisive for my work because, like others, I had been toying for some time with the idea of taking my art into the street, of making it more popular.10

Soto’s formula was nearly infallible: first, destroy form and, with it, composition by means of seriality; next, dematerialize the art object and turn it into vibration; finally, leave viewers open space in which to reinvent themselves. Of course, that formula can only be postulated in retrospect; the artist had to spend many years experimenting, facing challenges regarding both what he had already done and where he was going, before he was able to articulate what now seems like the impeccable, indeed almost mathematical, development of an art that was at the forefront of the avant-garde in Europe for a full two decades. To look at Soto through the lens of our times, I wanted to begin with a description of what was at play in those first works in which he was able to create the “illusion” of shattering form through analysis and dissection of perception. Consider how today Alexander Alberro describes Espiral, one of Soto’s fundamental works from that time: Materiality and immateriality are in tension, but in a purely visual manner. Soto has no evident interest in the inherent physical properties of the materials. Moreover, the fragile and dematerialized optical effects that challenge the eye’s power to control what it sees intensify and decrease depending on the spectator’s position. As the spectator ambulates laterally across the work, the lines of the spirals seen against the luminous white ground join and separate, and the two layers alternately contract and expand. The incessant rippling effect of this work differs significantly from the optical effects obtained by the mere repetition of elements on a flat surface in Soto’s art of the previous two or three years..11

That work ushered in a series to which Soto’s interest in dematerialization and relationality would be central. In the words of the always-eloquent artist:

I am not interested in the connections between things, only in their relationships. I am not interested in how colors or lines are connected. Relationships are worth more than connections. ... My work is essentially relationship. Not between two elements of the work itself, but between the principle that governs the work—for instance, dematerialization—and a general law of the universe that determines everything.12

This was one of the most ambitious programs of the period. It encompassed “fundamental concepts like fugacity, dematerialization, instability, the invisible, the environment, permutation, undulation, ubiquity and randomness”13 concepts paradigmatic to Soto’s research as a whole and reflected in a work from 1956 featured in this exhibition, a work from the series called Estructuras Cinéticas de Elementos Geométricos. Produced after his first kinetic structures from the late 1950s, the Vibraciones series is unquestionably a milestone in Soto’s research. No piece could better represent it than Vibración pura, a work from 1960 featured in this exhibition. In this work, the feverish activity of the extremely irregular support in the background becomes something like a camouflage for the twisted metal rods suspended in front of it. In the unique vibration produced, the rods seem to emerge from the support, as if they had been dug out of it, rather than floating in front of it. Soto spoke of these pieces in terms different from the culmination connotations used by legions of his followers and experts in his work. It is perhaps because of their greater affinity with works by major figures in the French New Realism and the Informalist movements, led by artists very close to Soto (Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely, and Lucio Fontana, among others), that this series of early vibrations has been particularly coveted by collectors and museums alike. In an interview with the most important art magazine of the time in the country of his birth, Soto spoke of those artists, also known as Neorealists: The destruction of form imposed by the Informalists was of great interest to me, in a way, but I realized that what they were proposing was the destruction of form as a solid body, by liquefying it. I, on the other hand, was attempting to destroy matter in order to transform it into energy. I did not wish to extol natural elements like branches, or nets and ropes, but to prove that their matter could be transformed into energy. Energy not in the scientific sense, but as I conceived it: a state of sensibility.14

Soto thus distanced himself from these artists and explained that his concerns differed from those of the Informalists. Throughout his career, Soto was able to put into practice this idea of the transformation of matter into energy thanks, fundamentally, to the groundbreaking discovery of vibration that makes his work unmistakable. Vibration was his identifying stamp to such an extent that Soto himself considered this phase a singular period in all his work. “All I cared about [at that time],” Soto said, “was to show to myself that my idea did not depend on a certain way of doing things. ... I felt the need to prove to myself that I could make use of anything at all in my work. The idea was to incorporate things very mundane but also highly formal (scraps of wood, pieces of wire, needles, bars, and tubes), to disintegrate them entirely through pure vibration.”15 In short, his mastery, his virtuosity was such, by this phase, that he could make anything vibrate.

The dematerialization of the object and the relativization of perception are among the radical advances embraced by the contemporary art agenda to which Soto left an invaluable legacy. He unquestionably contributed to the constant reinvention and transformation of accepted notions of how to experience a work of art, an enormous challenge to the different visions of the world and our relationships with what’s most entrenched in that world. Perhaps it is best, in closing, to put it as the artist did: “The immaterial is the sensible reality of the universe. Art is the sensible knowledge of the immaterial. Becoming aware of the immaterial at the state of pure structure is to make the final step towards the absolute.

Venezuelan-born artist Jesús Rafael Soto trained at an art school in Caracas. In 1950 he moved to Paris, which remained his base until his death in 2005. In 1955 Soto participated in Le Mouvement (The Movement) at Galerie Denise René, the exhibition that effectively launched kinetic art. During the same decade, he began making linear, kinetic constructions using industrial and synthetic materials such as nylon, Perspex, steel, and industrial paint. Major exhibitions of Soto’s work have taken place at Signals London (1965); the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (1971); the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1974); and Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris (1979).

1 Rafael Pereira and Jesús Soto, “La experiencia del viejo matador: entrevista a Jesús Soto por Rafael Pereira,” Kalathos, no. 4 (October–November 2000).

2 In this article, Masotta makes reference to El Lissitsky’s 1926 essay “The Future of the Book,” which uses the term dematerialization as we do today. See Oscar Masotta, “After Pop, We Dematerialize,” in Listen, Here, Now! Argentine Art of the 1960s: Writings of the Avant-Garde, ed. Inés Katzenstein (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2004), p. 216. See as well Frank Popper, Introduction to Lumière et Mouvement (exh. cat. Paris: Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1967) and Jean Clay, “Le cinétisme est-il un académisme ?” Robho, no. 2 (November–December 1967).

3 According to Antonio Somaini, “This idea [that light is the fundamental artistic ‘medium’] led Moholy-Nagy to formu- late the thesis according to which all art forms—painting, sculpture, photography, cinema, design, stage design or archi- tecture—develop according to a teleologically oriented tendency that leads from stasis to motion, from opaqueness to transparency, and from different concrete materials towards a state of progressive dematerialization.”“The Surface Becomes a Part of the Atmosphere”: Light as Medium in László Moholy-Nagy’s Aesthetics of Dematerialization,” Screen 61, issue 2 (Summer 2020): p. 289

4 “Everything will be painted white to receive the pictorial climate of the sensibility of dematerialized blue” (my empha- sis). Excerpt from “Preparation and Presentation of the Exhibition on April 28, 1958 at the Iris Clert Gallery, 3 rue des Beaux-Arts, Paris,” in Overcoming the Problematics of Art: The Writings of Yves Klein, trans. Klaus Ottmann (Thompson, CT: Spring Publications, 2007), p. 47. Soto speaks of immateriality in Soto (exh. cat. Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1969), and of dematerialization in “Statements by Kinetic Artists,”

Studio International 173, no. 886 (February 1967): p. 60. 5 Jean Clay, “Soto, de l’art optique à l’art cinétique,” Soto (exh. cat. Paris: Galerie Denise René, 1967), quoted in Arnauld Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, trans. Martin Back and Thierry Noujaim (exh. cat. Perrotin: Paris, 2014), p. 156.

6 Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Fall 2004): p. 52.

7 Ibid., p. 62.

8 Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, trans. Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2002), p. 14.

9 See Mónica Amor, “La beauté est dans la rue ! Jesús Rafael Soto’s 1969 Public and Exceptional Foray,” in Soto. The Fourth Dimension (exh. cat. Bilbao: Guggenheim Museum, 2020), pp. 39–43.

10 Soto, quoted by Miyó Vestrini in “Jesús Soto: Venezuela es Uno de los Raros Paises de America Latina Donde Existe la Necesidad de Crear un Arte Nuevo,” El Nacional, July 24, 1971, p. 8, quoted in Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, p. 166.

11 Alexander Alberro, Abstraction in Reverse: The Reconfigured Spectator in Mid-Twentieth-Century Latin American Art (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), p. 118.

12 Soto, “Statements by Kinetic Artists,” p. 60.

13 Clay, “Le cinétisme est-il un académisme ?” quoted in Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, p. 165.

14 Soto, interview with Iván González, “Soto: liberar el material hasta que se vuelva tan libre como la música,” Imagen, no. 32 (September 1–15, 1968), p. 10, quoted in Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, p. 159.

15 Ariel Jiménez, Conversaciones con Jesús Soto (Caracas: Fundación Cisneros, 2001), p. 62.

16 Soto in Soto, 1969, p. 56, quoted in Pierre, “Chronology,” in Jesús Rafael Soto, p. 166.

| Jesús Rafael Soto | |

Opening reception :

March 5, 12 - 8pm

mpefm

U.S.A. art press release

Opening Hours:

TUESDAY - SATURDAY, 10AM - 6PM

You can make an appointment to view the exhibition here.

Opening Hours:

TUESDAY - SATURDAY, 10AM - 6PM

You can make an appointment to view the exhibition here.

QR of this press release

in your phone, tablet