"Lost & Found"

Jessica Diamond, Arnold J. Kemp, Kayode Ojo, Arthur Simms, Alexandria Smith

MARTOS GALLERY

41 Elizabeth Street New York, NY 10013+1 212 560 0670 e-mail:

Multiple location : New York NY Los Angeles CA

February 5 - March 13, 2021

Among the works in this exhibition, whose naming itself may be considered in some sense an invitation to become purposefully, pleasurably lost:

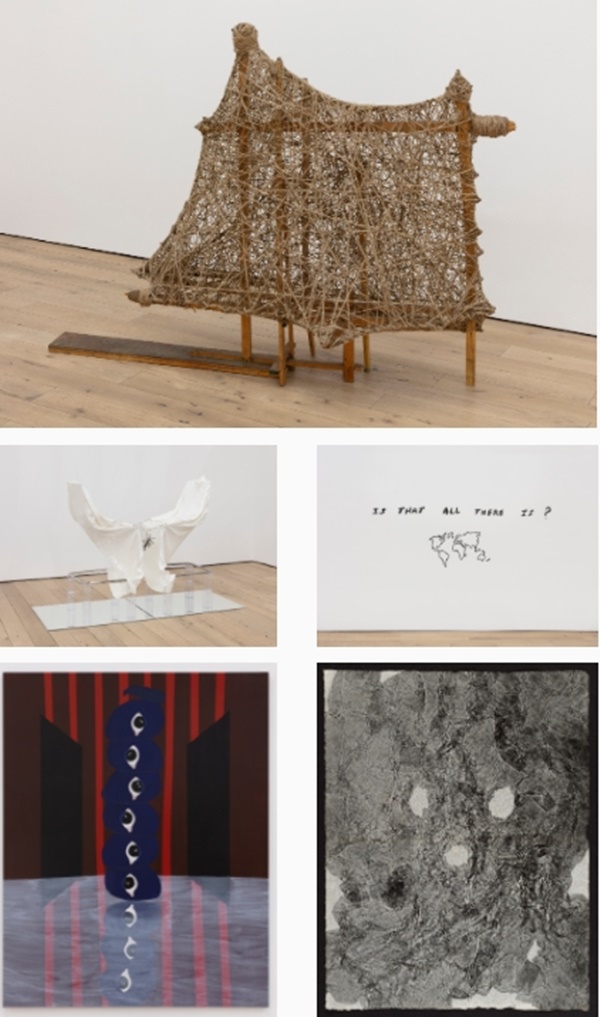

Jessica Diamond, Is That All There Is?, a wall painting from the Orwellian year of 1984 (a book written in 1948) that presents an image of the world, all of the continents, in a diminutive scale in relation to the large, wide text above, and to us before the oceanic wall. Given the endangered state of the planet today, climate change, hotter temperatures, rising seas, caused and accelerated by our actions and inaction, many would answer: Yes, that's all we have. Let's not destroy it so cavalierly. When this work was initially conceived, the artist may not have had any idea of a world so imperiled more than thirty years later, but here we are, and her work continues to resonate, as all engaged art does, for troubled times. Diamond must also have had in mind the signature song of Peggy Lee, which registers a world-weary resignation to disappointment, its inevitability—a lassitude within latitudes?—which asks, in childhood reminiscence: Is that all there is to a circus?

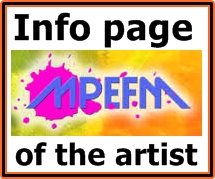

Arnold J. Kemp<, two formidable canvases presented side-by-side, composed of spidery webs, entangled, layered lines, black on black, depth and transparency—in abeyance on their way to full immersion. These near-monochromes evidence their very making, underpainting brought to the fore, a staging of hide and seek in shadow and darkness, to revel in and question the abstract, an unseen finger points to the viewer to ask, And what do you represent? These paintings find correspondence with three prints from Index, the artist's silvery flattened masks, faceless faces echoing hoods, eyeless, haunted, otherworldly. What has the artist indexed for us? Nothing less than a whole litany of loss? Masks and hoods have featured in Kemp's work for the past twenty years. The masks in his Slow Season Ritual Drawings (2016), although having flourishes of floral and roseate color, are emblematic of scars specked with blood. Incantation, a ritual recitation to elicit a healing, magical effect.

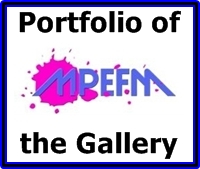

Kayode Ojo's figurative sculptures are surrogate feminine bodies of alien glamour, reduced to drapery and flowing blonde hair, bodies with no corporeality save for wardrobe—an outer, protective skin—luxuriant wigs, and armature, often music stands. (Let's face the music ... and dance.) Where bodies are doubled they are reciprocal, uneasily so, possibly in a state of arrest, handcuffed together. Ice Queen (2021) imagines a frosty white apparition, a body double, a sequined being, arm in arm, in concert: music for two and four hands? Yet paralyzed, frozen in place, poised on unstable ground. This is an artist whose concerns for actual bodies in real space can be seen as reflected in his insistence on presenting his works in precarious balance, at times on sheets of glass—thin ice—a precipice of fragility and violence. In this, despite their haute-luxe alienation, these bodies could not be more true to life.

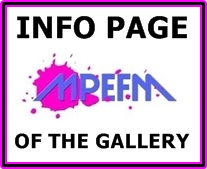

Arthur Simms, in an interwoven assemblage, a bell, a horn, toys, a pair of child's ice skates and more, all bound together, add up to ... what exactly? Or refer to whom, to the artist and his history, to his ongoing activity: Ego Sum, Portrait of Arthur Simms as a Junk Collector (1994). From the front, its dense skeins suggest a materialist action painting-object; from behind, a complex collage/combine with photos and drawings, felt and pressed tin. Here, a slender rope dangles from a simple gibbet at the top, the dingy white skates are hung by their laces below, blades dulled over time, the bell of the horn, shiny but silent. A similarly woven work, which might be a sailing ship, permeable sails and rigging made of rope, is also a matter of embodiment, Portrait Of An Angry Man With A Gun (1992). Among Simms's Black Caravaggio collages (2003-08) there are references to art history and Black history, the most exemplary his pairing of the great late 16th/early 17th century painter and the American abolitionist, author, and orator, the former slave Frederick Douglass.

Alexandria Smith's totemic Meeting of the Minds (2018) rises above the gallery, a sideways—sidereal? — stack of three heads and six eyes, with another three mirrored in the glacial ground below. Allusions to other worlds beyond and the heavens above, inhabited by seemingly extraterrestrial life, are evidenced by the Cycloptic heads that impassively and disconcertingly return our gaze in her diptych, the stars between (2019). We encounter more human-like, identifiably female forms, nipple to nipple, their heads in the clouds and rigid, extended legs, seemingly comical but occupying a stiffening of death in A Rigamortis Paradise (2018). The inhabitants of her world, for all their strangeness are recognizable to us. Are they in search of salvation and maybe enlightenment along the way? Two fingers point to a bare, but glowing light bulb in The Seekers (2019). They could be our own.

Jessica Diamond, Is That All There Is?, a wall painting from the Orwellian year of 1984 (a book written in 1948) that presents an image of the world, all of the continents, in a diminutive scale in relation to the large, wide text above, and to us before the oceanic wall. Given the endangered state of the planet today, climate change, hotter temperatures, rising seas, caused and accelerated by our actions and inaction, many would answer: Yes, that's all we have. Let's not destroy it so cavalierly. When this work was initially conceived, the artist may not have had any idea of a world so imperiled more than thirty years later, but here we are, and her work continues to resonate, as all engaged art does, for troubled times. Diamond must also have had in mind the signature song of Peggy Lee, which registers a world-weary resignation to disappointment, its inevitability—a lassitude within latitudes?—which asks, in childhood reminiscence: Is that all there is to a circus?

Arnold J. Kemp<, two formidable canvases presented side-by-side, composed of spidery webs, entangled, layered lines, black on black, depth and transparency—in abeyance on their way to full immersion. These near-monochromes evidence their very making, underpainting brought to the fore, a staging of hide and seek in shadow and darkness, to revel in and question the abstract, an unseen finger points to the viewer to ask, And what do you represent? These paintings find correspondence with three prints from Index, the artist's silvery flattened masks, faceless faces echoing hoods, eyeless, haunted, otherworldly. What has the artist indexed for us? Nothing less than a whole litany of loss? Masks and hoods have featured in Kemp's work for the past twenty years. The masks in his Slow Season Ritual Drawings (2016), although having flourishes of floral and roseate color, are emblematic of scars specked with blood. Incantation, a ritual recitation to elicit a healing, magical effect.

Kayode Ojo's figurative sculptures are surrogate feminine bodies of alien glamour, reduced to drapery and flowing blonde hair, bodies with no corporeality save for wardrobe—an outer, protective skin—luxuriant wigs, and armature, often music stands. (Let's face the music ... and dance.) Where bodies are doubled they are reciprocal, uneasily so, possibly in a state of arrest, handcuffed together. Ice Queen (2021) imagines a frosty white apparition, a body double, a sequined being, arm in arm, in concert: music for two and four hands? Yet paralyzed, frozen in place, poised on unstable ground. This is an artist whose concerns for actual bodies in real space can be seen as reflected in his insistence on presenting his works in precarious balance, at times on sheets of glass—thin ice—a precipice of fragility and violence. In this, despite their haute-luxe alienation, these bodies could not be more true to life.

Arthur Simms, in an interwoven assemblage, a bell, a horn, toys, a pair of child's ice skates and more, all bound together, add up to ... what exactly? Or refer to whom, to the artist and his history, to his ongoing activity: Ego Sum, Portrait of Arthur Simms as a Junk Collector (1994). From the front, its dense skeins suggest a materialist action painting-object; from behind, a complex collage/combine with photos and drawings, felt and pressed tin. Here, a slender rope dangles from a simple gibbet at the top, the dingy white skates are hung by their laces below, blades dulled over time, the bell of the horn, shiny but silent. A similarly woven work, which might be a sailing ship, permeable sails and rigging made of rope, is also a matter of embodiment, Portrait Of An Angry Man With A Gun (1992). Among Simms's Black Caravaggio collages (2003-08) there are references to art history and Black history, the most exemplary his pairing of the great late 16th/early 17th century painter and the American abolitionist, author, and orator, the former slave Frederick Douglass.

Alexandria Smith's totemic Meeting of the Minds (2018) rises above the gallery, a sideways—sidereal? — stack of three heads and six eyes, with another three mirrored in the glacial ground below. Allusions to other worlds beyond and the heavens above, inhabited by seemingly extraterrestrial life, are evidenced by the Cycloptic heads that impassively and disconcertingly return our gaze in her diptych, the stars between (2019). We encounter more human-like, identifiably female forms, nipple to nipple, their heads in the clouds and rigid, extended legs, seemingly comical but occupying a stiffening of death in A Rigamortis Paradise (2018). The inhabitants of her world, for all their strangeness are recognizable to us. Are they in search of salvation and maybe enlightenment along the way? Two fingers point to a bare, but glowing light bulb in The Seekers (2019). They could be our own.

|

Kayode Ojo |

| Jessica Diamond |

| Arnold J. Kemp |

| Arthur Simms |

| Alexandria Smith |

Opening reception:

Tuesday, September 15, 10am - 6pm

mpefm

USA art press release

Gallery Hours:

Tuesday - Saturday, 10 - 6PM

QR of this press release

in your phone, tablet