"Friday Feature"

Chuck Close, Ed Moses, Wayne Thiebaud, Ed Ruscha

Leslie Sacks Contemporary

Bergamot Station 2525 Michigan Avenue, B6 Santa Monica, California 90404T: (310) 264-0640 F: (310) 264-0740 e-mail:

1 > 30 November, 2017

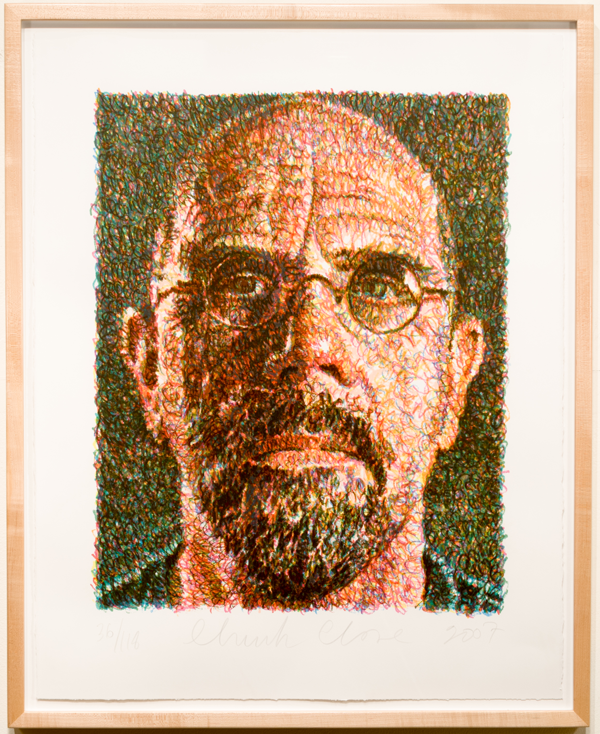

Chuck Close, Self-Portrait, 2007, screenprint 38 x 30 inches, edition of 118, signed and numbered

Working with an array of assistants, printmakers and publishers, Close has explored just about every conceivable type of printmaking technique, from etching, aquatint, lithography, handmade paper, direct gravure, silkscreen, traditional Japanese woodcuts to reduction linocuts, among many others. While this formal exploration has taken place, Close has stuck to the same subject throughout his career - the portrait, both the self-portrait and images of friends, family and fellow artists - and maintained, with very few exceptions, almost exactly the same composition, face-on to the camera and cropped down to head and shoulders. After his early success with his paintings and an association with the photorealists of the late 1960s, Close was seduced by printmaking when he created the mezzotint Keith [1972]. The serial quality of making a large-scale print, where the artist would produce one section of the image, then make a print, then continue until the final result was a series that slowly built up to a final image, became the conceptual basis for the rest of his career.

--Andrew Frost, "Chuck Close review - analogue printmaking explores a digital era" at the

Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia, The Guardian, Arts & Design, 18 November 2014

View additional works by Chuck Close

Chuck

Close

--Andrew Frost, "Chuck Close review - analogue printmaking explores a digital era" at the

Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia, The Guardian, Arts & Design, 18 November 2014

View additional works by Chuck Close

Chuck

Close

Ed Moses, Bad Cubis-1, 2014, acrylic on canvas, 60 x 48 inches

Ed Moses has proved the definition of "artist". With a restless promise that won him a solo show in 1957 at the then nascent Ferus Gallery, he never ceased to experiment. He worked with latex, to great sales and acclaim, but reverted to painting. He introduced the grid, investigating its infinite possibilities through variations that he attributes to accident but that speak to sequential resolutions arrived at through exploration and deliberation. When he needed more reach, he added panels; when he wanted pop, he inserted metals. Around 1987, the grid morphed into squiggles - he called them "worms" - and when he exhausted their contribution began juxtaposing materials that resisted each other. He manipulated his process by scratching or scraping the surfaces and switching to tools that allowed him to drag and layer more paint. A retrospective at [Los Angeles MOCA] served to galvanize new directions; pushing back against the dark undertone of "memorial", Moses moved radically on, to incorporate fluorescence, glitter and elements sprayed through netting. Lest abstraction sideline him, he explored innuendo, overtly sexual imagery that he floated into allusion. He flirted with sponge-painting, snap-line painting, erasure. Periodically, like a dybbuk, the grid returned; sometimes diagonal, sometimes blurred, and always crisscrossed in a vertigo-inducing ambiguity of interlocked planes. The process moved to craquelure, the effect achieved through that famous accident, now recaptured by thrusting a fist or elbow through layers of dried paint, applying a medium that Moses called his "secret sauce", and then layering more paint until, "wham!" it worked.

--Jill Spalding, Ed Moses: Painting as Process, Studio International, New York, September 25, 2016

View additional works by Ed Moses

Ed Moses

--Jill Spalding, Ed Moses: Painting as Process, Studio International, New York, September 25, 2016

View additional works by Ed Moses

Ed Moses

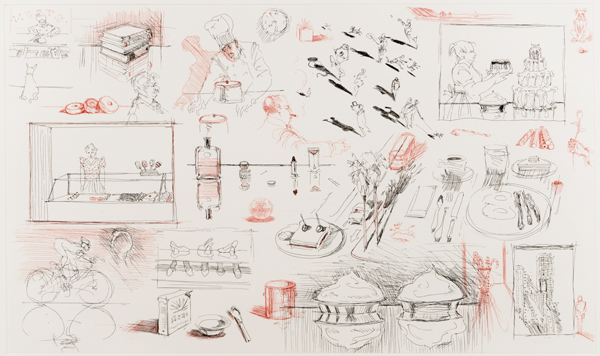

Detail: Wayne Thiebaud, Sketches, 1995, hard-ground etching 21 3/4 x 30 inches, edition of 50, signed and numbered

Thiebaud's imagery is ultimately the result of three interconnected elements: observation, recollection and imagination. He once talked with the art critic Bryan Doherty, about Hopper's working methods, particularly in making his cityscapes, and learned that the earlier artist made multiple sketches from observations of a model or a site and then synthesized selections later into a painting. Thiebaud found this valuable for his city views and landscapes where what he saw could be transformed into pictorial artifice. Even the foods and confections he found in shop windows became reduced to pure forms, primarily circles, triangles, rectangles and squares. On canvas they sit on counters, tables or shelves, often never fully defined, often un-edged. The white ground frequently flows from receding surface to background wall, only overlapping forms and shadow angles hint at depth. The reconstituting of the unknown world into works of abstract purity is one of Thiebaud's unrivaled slights of hand and mind.

--John Wilmerding, Wayne Thiebaud: The Emperor of Ice Cream, Aquavella, New York, Rizzoli, 2012, pg 29-30

View additional works by Wayne Thiebaud

Wayne Thiebaud

--John Wilmerding, Wayne Thiebaud: The Emperor of Ice Cream, Aquavella, New York, Rizzoli, 2012, pg 29-30

View additional works by Wayne Thiebaud

Wayne Thiebaud

Ed Ruscha, Yes, 1984, lithograph, 22 3/8 x 30 1/8 inches Edition of 25, signed and numbered

In the world of Edward Ruscha's art, language has simultaneously assumed the dual roles of word and image. Ruscha's nonhierarchical treatment of language is in this sense democratic--if the word chooses to assert itself as picture, so be it. On the other hand, if it connotes a meaning (ranging from a forehead-slapping "of course!" gleaned from a few seconds of analysis to the resolutely enigmatic), that works, too. Democracy has been an attitude--perhaps a tenet--of Ruscha's work from the moment he decided to become a visual artist. Like the work of Pop artists to whom he is often compared, his first paintings were inspired by icons of mass culture, their brand associations emblazoned across the canvases as if they were billboards: ANNIE, SPAM, STANDARD, 20th CENTURY FOX. Everything was worthy of consideration artistic subject, as long as it had the promise of a visual message, and if lucky, a double entendre.

--Siri Enberg, Ed Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonne, Volume 2, Out of Print

View additional works by Ed Ruscha--Siri Enberg, Ed Ruscha: Catalogue Raisonne, Volume 2, Out of Print

Ed Ruscha