"The Iris of Beasts"

Wang Liang-Yin

curated by WANG Rui-Xu

LIN & LIN GALLERY

1F, No.16, Dongfeng St., Taipei, TaiwanTEL 886 2 2700 6866 FAX 886 2 2700 6766 e-mail:

Multiple location : Beijing Taipei

March 6 > April 24, 2021

Chen Kuang-Yi, Ph.D., Université Paris X-Nanterre; Dean of the Fine ArtCollege and Professor of the Department of Fine Arts at the National TaiwanUniversity of Arts

Like any other conscientious professional painter, Wang Liang-Yin holds a solo exhibition every other year. Thus far, these include her 2014 Happy Birthday, My Dear at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum; 2016 Gift and Dust; 2018 The End of the Rainbow; and her most recent exhibition, postponed to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, The Iris of Beasts. Her regular creative production and exhibition, as well as the quality and quantity of the paintings that she presents, are clear indicators of her determination and professional ambition. However, the ease or difficulty of producing any artwork, especially that of a painter, certainly cannot be determined by any conventional logic. Wang's high production rate suggests one of two things. Either she is a habitual painter whose skill and standardized process have completely freed her from the art form's difficulties, or the paradoxes hidden in the means and ends, or in the form and content, of her creative practice have resulted in her constant engagement with a difficult to attain balance between polar opposites, and thus inexhaustible creative drive. I think the latter is a more likely explanation.

Wang Liang-Yin no doubt revels in extravagant beauty, as her work has never been plain, and her skills have been called consummate. Every one of her recent paintings, based on her use of automatism, is vivid and uninhibited, and in these unplanned compositions, she gives free rein to her instincts by applying large swaths of flowing and dripping acrylic paint in sweeping gestures, which results in limitless layers of opaque and transparent richness. If she were to stop there, the work would be called abstract expressionism or lyrical abstraction, but she creates all this beauty just to prime the canvas. As abstraction is not her goal, she ultimately organizes concrete images from out of this colorful and expressive material. In this way, Wang uses paint and painting tools both in the traditional sense to create images, and in another way that highlights the existence and special qualities of the paint itself. In other words, she represents reality while presenting the reality she is actually feeling at the time of creating. She therefore stresses a dual role for the paint she uses, and produces a paradox with regard to intent and technique. In earlier work, she represented more than presented, but recently, presentation nearly overwhelms representation. This competition and balancing between representation and presentation, however, makes the work much more noisy and exciting. Viewers can barely recognize her forms due to their constant undoing by colorful primer, and the elements she uses to manifest her forms also seem to threaten their very existence. Such paradoxes destabilize the spatial reality and images in her paintings, and the more extravagant her paintings, the more fragile her images—and the more transcendental her spaces—become. But she still strives to maintain a balance between the two, lest her images be completely swallowed up and cast into obscurity.

Paradox is also expressed in Wang's use of color. It is a fact that a full spectrum of vivid colors will quickly catch one's attention, but gorgeous rainbows are also reflected by dust and ashes, as well as slide over the surface of bubbles, if only for a moment. In the same way, joyously noisy colors mix in or flow out of sorrowful turbid shades in Wang's paintings, and her bright and beautiful subject matter is always accompanied by a dark menacing background. Thin, running paint in high contrast tints and hues delight and threaten, making her work seem like a children's horror story.

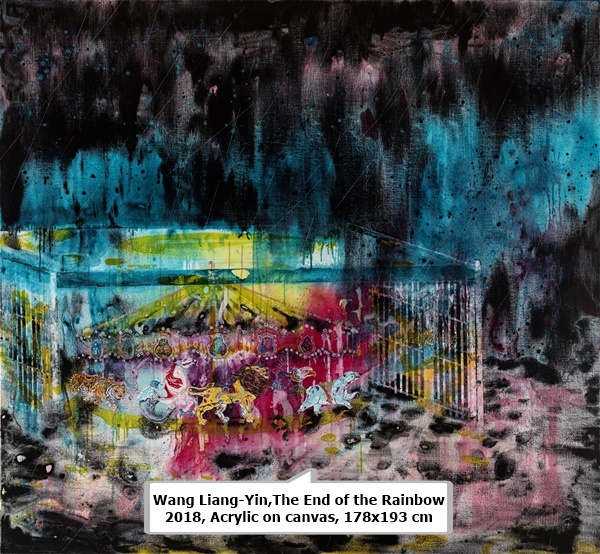

Wang likes to paint celebrations and themes or symbols related to them. For her 2014 exhibition Happy Birthday, My Dear, she collected a number of birthday party scenes, which include many showy and extravagant birthday cakes, peaches, and other celebratory props in various impromptu states, as if the party has just ended and everyone has left. Her portrayal of birthday parties conveys the loneliness felt after the joy of a group celebration has passed or the emptiness of unattainable birthday wishes, thus raising big questions about the meaning of life. Next, in her 2016 exhibition Gift and Dust, we see love birds and a wedding present, and in her 2018 The End of the Rainbow, Christmas trees, circuses, a lonely carousel, and dilapidated playgrounds appear. In all human societies, commemorative ceremonies and celebrations have served no other purpose than to fabricate exaggerated atmospheres, boost morale, and make life seem colorful and brimming with enthusiasm, and such themes emerged in an endless stream in sixteenth and seventeenth century European genre painting. However, mass celebrations and carnivals could also devolve into collective disorder, as in Pieter Bruegel the Elder's 1559 painting The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, or in his 1565 – 68 The Wine of Saint Martin's Day. Other ceremonies that had been intended as blessings and considered affecting were also depicted as ugly customs of broken dreams, such as those in William Hogarth's 1743 – 45 series of paintings Marriage A-la-Mode. However, Wang's style of celebration is closer to Francisco Goya's c. 1793 – c. 1819 The Burial of the Sardine, which presents the funeral of Carnival.

In his essay A Philosophy of Toys, Baudelaire wrote, "The toy is the child's earliest initiation into art, or rather for him it is the first concrete example of art." As an object, a toy oscillates between being practical and impractical, or between art and non-art, because if it has any function at all, it is not to fulfill any of life's material needs, but to enlighten and expand its owner's mind through creativity, and to satisfy the impulse to create. Toys often are symbols of childhood and play roles in childhood rituals, but they also serve as spokespersons of adult society. Starting in the 14th century, boys and girls were often depicted holding toys in the family portraits of nobles. In these paintings, girls are usually playing with dolls, carts, or balls; and boys with bamboo or wooden horses, tops, iron rings, or rattle drums. In Bruegel the Elder's 1560 Children's Games, one hundred and twenty-two boys and seventy-eight girls are playing with ninety-one different kinds of toys in a large town square. Although the painting's subject matter is not without precedent, some of its interpretations have quickly transcended reality. The seventeenth century Dutch poet Jacob Cats wrote the lines, "The world and its complete structure, / Is nothing but a children's game;" and "You will find there, I know it well / Your own folly in children's games."Jean-Siméon Chardin, in his 1739 painting The Governess, depicted toys strewn on the floor and a child holding a book, suggesting an opposition between the two childhood activities of playing and learning. In any case, toys have always maintained relationships between reality and unreality in the dichotomies of childhood versus adulthood or play versus work, and are often used as accessories in allegorical paintings, genre paintings, and portrait paintings, but rarely appear in still life paintings.

Wang Liang-Yin's depictions of toys in her paintings differ from what is seen in art historical traditions. For her 2014 exhibition, which centered on a birthday theme, she painted birthday props in several works, such as Crown Hat, Angel, Sunglasses with Candles, and Starry Hat, which showed her gradual approach to a kind of voluntary fetishism. These paintings contain fewer figures and more objects, and the objects exist independently of their owners, thus suggesting different meanings. For each exhibition, she depicts objects that are related to the exhibition theme, including food, gifts, or decoration such as a rainbow slinky, balloons, masks, wind chimes, mobiles, wind-up toys, molds for making plastic dolls, vintage tin toys, toy planes, tin Christmas trees, plush dolls, bubble machines or wands, eye glasses, lucky cats, and charms, which are all unique and tactile. Regardless of their material or age, these toys are always enlarged, presented in a portrait-like fashion, and dominate her paintings. She uses her distinctive painting technique of bedazzling and glittering, thus rendering these toys as iridescent, nonpareil dreams. Her perspective is hardly meaningless, as everything a child sees, especially toys, appears monumental. In his essay Meditations on a Hobby Horse, Ernst Gombrich wrote, "Let us assume that the owner of the stick on which he proudly rode through the land decided in a playful or magic mood-and who could always distinguish between the two?" Imagination brings a toy to life, and real life and infinite magic allow us to temporarily escape from reality and create new individual or collective myths.

Although we do not know if these toys originally belonged to Wang, they were used by someone and therefore are still vessels for memories. Some of her exquisite tin toys evoke toy manufacturing in Taiwan from the 1950s and 1960s, an era before plastic toys and handheld game consoles appeared. They not only indirectly speak to a specific social or economic status, but also remind us that once rendered obsolete, toys will be discarded by their owners. As Wang's work is obviously autobiographical, it can be assumed that she is telling stories with her own toys, or at least with ones she has collected.

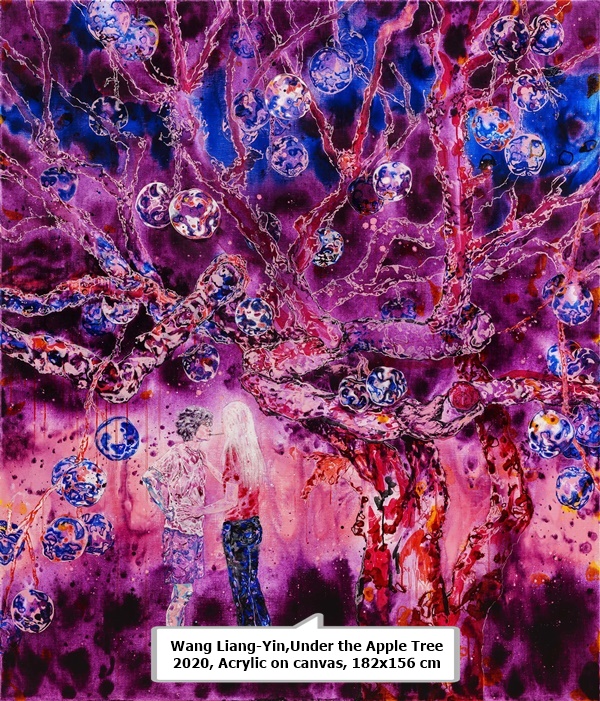

Wang Liang-Yin does indeed tell stories. Her artwork is filled with stories, and this may be the main reason for her unwillingness to adopt abstraction. Her custom in every exhibition has been to present small-sized paintings of objects, medium-sized paintings, possibly landscapes or portraits, and one large-scale thematic masterpiece. This arrangement of different subject matter, canvas size, and ways of hanging paintings in the exhibition venue constructs intertextual relationships among the works, and thus serves as a way of developing narratives and scenes. Furthermore, each exhibition has a theme and related system of symbols, which creates a decoding game for the audience. Compared with previous exhibitions, The Iris of Beasts is clearly more literary, in that Wang Liang-Yin has blends in two main texts—the Bible, including several of its symbols and metaphors, such as the apple or forbidden fruit, trumpet blowing angels, the great flood, and Noah's Ark; and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's The Little Prince with the airplane, planet, rose and fox. To these two texts, which she deploys to talk about loneliness, desire, love, judgment, destruction, and redemption, the artist, deliberately or not, has added herself and her story to the exhibition. But what story is that?

When visiting the exhibition, stand in front of her 1.8 meter high and 4 meter long work titled Angels, Apples, Beasts and take note of the flood blotting out the sky. It is strange that the various pairs of beasts have not boarded the ark, but are floating or submerged in the vast flood waters. And at the center of the painting, she depicted several floating eyeballs and their delicate irises. Allegorical or prophetic painting is full of details, some of which are recognizable, such that their effects oscillated between consciousness and unconsciousness, realism and surrealism, or reality and imagination. The deconstruction, altering, and rewriting of a text have opened the boundaries of reading and led to different interpretations, and in her case, perhaps these interpretations are the result of Wang Liang-Yin's insistence on using paradoxes and divergences as her creative strategies.

Wang has been not only in Taiwan but also overseas for exhibitions such as New York, Germany, UK, Japan, Jakarta, Korea, and China. She had solo exhibitions Happy Birthday, My Dear at Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taipei in 2014, The End of the Rainbow at Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, Taipei in 2018. Wang's artworks are collected by National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Art Bank Taiwan, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Long Yen Foundation, Taipei National University of the Arts, Taichung County Seaport Art Center, and Sunpride Foundation, and are not only selected by Kaohsiung Award but also won the first prize of NewPerspective Art in Taiwan Dimensional Creation Series, Long Yen Foundation Creative Arts Award, Chang Hsing Lung Award and so on.

Like any other conscientious professional painter, Wang Liang-Yin holds a solo exhibition every other year. Thus far, these include her 2014 Happy Birthday, My Dear at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum; 2016 Gift and Dust; 2018 The End of the Rainbow; and her most recent exhibition, postponed to 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, The Iris of Beasts. Her regular creative production and exhibition, as well as the quality and quantity of the paintings that she presents, are clear indicators of her determination and professional ambition. However, the ease or difficulty of producing any artwork, especially that of a painter, certainly cannot be determined by any conventional logic. Wang's high production rate suggests one of two things. Either she is a habitual painter whose skill and standardized process have completely freed her from the art form's difficulties, or the paradoxes hidden in the means and ends, or in the form and content, of her creative practice have resulted in her constant engagement with a difficult to attain balance between polar opposites, and thus inexhaustible creative drive. I think the latter is a more likely explanation.

Wang Liang-Yin no doubt revels in extravagant beauty, as her work has never been plain, and her skills have been called consummate. Every one of her recent paintings, based on her use of automatism, is vivid and uninhibited, and in these unplanned compositions, she gives free rein to her instincts by applying large swaths of flowing and dripping acrylic paint in sweeping gestures, which results in limitless layers of opaque and transparent richness. If she were to stop there, the work would be called abstract expressionism or lyrical abstraction, but she creates all this beauty just to prime the canvas. As abstraction is not her goal, she ultimately organizes concrete images from out of this colorful and expressive material. In this way, Wang uses paint and painting tools both in the traditional sense to create images, and in another way that highlights the existence and special qualities of the paint itself. In other words, she represents reality while presenting the reality she is actually feeling at the time of creating. She therefore stresses a dual role for the paint she uses, and produces a paradox with regard to intent and technique. In earlier work, she represented more than presented, but recently, presentation nearly overwhelms representation. This competition and balancing between representation and presentation, however, makes the work much more noisy and exciting. Viewers can barely recognize her forms due to their constant undoing by colorful primer, and the elements she uses to manifest her forms also seem to threaten their very existence. Such paradoxes destabilize the spatial reality and images in her paintings, and the more extravagant her paintings, the more fragile her images—and the more transcendental her spaces—become. But she still strives to maintain a balance between the two, lest her images be completely swallowed up and cast into obscurity.

Paradox is also expressed in Wang's use of color. It is a fact that a full spectrum of vivid colors will quickly catch one's attention, but gorgeous rainbows are also reflected by dust and ashes, as well as slide over the surface of bubbles, if only for a moment. In the same way, joyously noisy colors mix in or flow out of sorrowful turbid shades in Wang's paintings, and her bright and beautiful subject matter is always accompanied by a dark menacing background. Thin, running paint in high contrast tints and hues delight and threaten, making her work seem like a children's horror story.

Wang likes to paint celebrations and themes or symbols related to them. For her 2014 exhibition Happy Birthday, My Dear, she collected a number of birthday party scenes, which include many showy and extravagant birthday cakes, peaches, and other celebratory props in various impromptu states, as if the party has just ended and everyone has left. Her portrayal of birthday parties conveys the loneliness felt after the joy of a group celebration has passed or the emptiness of unattainable birthday wishes, thus raising big questions about the meaning of life. Next, in her 2016 exhibition Gift and Dust, we see love birds and a wedding present, and in her 2018 The End of the Rainbow, Christmas trees, circuses, a lonely carousel, and dilapidated playgrounds appear. In all human societies, commemorative ceremonies and celebrations have served no other purpose than to fabricate exaggerated atmospheres, boost morale, and make life seem colorful and brimming with enthusiasm, and such themes emerged in an endless stream in sixteenth and seventeenth century European genre painting. However, mass celebrations and carnivals could also devolve into collective disorder, as in Pieter Bruegel the Elder's 1559 painting The Fight Between Carnival and Lent, or in his 1565 – 68 The Wine of Saint Martin's Day. Other ceremonies that had been intended as blessings and considered affecting were also depicted as ugly customs of broken dreams, such as those in William Hogarth's 1743 – 45 series of paintings Marriage A-la-Mode. However, Wang's style of celebration is closer to Francisco Goya's c. 1793 – c. 1819 The Burial of the Sardine, which presents the funeral of Carnival.

In his essay A Philosophy of Toys, Baudelaire wrote, "The toy is the child's earliest initiation into art, or rather for him it is the first concrete example of art." As an object, a toy oscillates between being practical and impractical, or between art and non-art, because if it has any function at all, it is not to fulfill any of life's material needs, but to enlighten and expand its owner's mind through creativity, and to satisfy the impulse to create. Toys often are symbols of childhood and play roles in childhood rituals, but they also serve as spokespersons of adult society. Starting in the 14th century, boys and girls were often depicted holding toys in the family portraits of nobles. In these paintings, girls are usually playing with dolls, carts, or balls; and boys with bamboo or wooden horses, tops, iron rings, or rattle drums. In Bruegel the Elder's 1560 Children's Games, one hundred and twenty-two boys and seventy-eight girls are playing with ninety-one different kinds of toys in a large town square. Although the painting's subject matter is not without precedent, some of its interpretations have quickly transcended reality. The seventeenth century Dutch poet Jacob Cats wrote the lines, "The world and its complete structure, / Is nothing but a children's game;" and "You will find there, I know it well / Your own folly in children's games."Jean-Siméon Chardin, in his 1739 painting The Governess, depicted toys strewn on the floor and a child holding a book, suggesting an opposition between the two childhood activities of playing and learning. In any case, toys have always maintained relationships between reality and unreality in the dichotomies of childhood versus adulthood or play versus work, and are often used as accessories in allegorical paintings, genre paintings, and portrait paintings, but rarely appear in still life paintings.

Wang Liang-Yin's depictions of toys in her paintings differ from what is seen in art historical traditions. For her 2014 exhibition, which centered on a birthday theme, she painted birthday props in several works, such as Crown Hat, Angel, Sunglasses with Candles, and Starry Hat, which showed her gradual approach to a kind of voluntary fetishism. These paintings contain fewer figures and more objects, and the objects exist independently of their owners, thus suggesting different meanings. For each exhibition, she depicts objects that are related to the exhibition theme, including food, gifts, or decoration such as a rainbow slinky, balloons, masks, wind chimes, mobiles, wind-up toys, molds for making plastic dolls, vintage tin toys, toy planes, tin Christmas trees, plush dolls, bubble machines or wands, eye glasses, lucky cats, and charms, which are all unique and tactile. Regardless of their material or age, these toys are always enlarged, presented in a portrait-like fashion, and dominate her paintings. She uses her distinctive painting technique of bedazzling and glittering, thus rendering these toys as iridescent, nonpareil dreams. Her perspective is hardly meaningless, as everything a child sees, especially toys, appears monumental. In his essay Meditations on a Hobby Horse, Ernst Gombrich wrote, "Let us assume that the owner of the stick on which he proudly rode through the land decided in a playful or magic mood-and who could always distinguish between the two?" Imagination brings a toy to life, and real life and infinite magic allow us to temporarily escape from reality and create new individual or collective myths.

Although we do not know if these toys originally belonged to Wang, they were used by someone and therefore are still vessels for memories. Some of her exquisite tin toys evoke toy manufacturing in Taiwan from the 1950s and 1960s, an era before plastic toys and handheld game consoles appeared. They not only indirectly speak to a specific social or economic status, but also remind us that once rendered obsolete, toys will be discarded by their owners. As Wang's work is obviously autobiographical, it can be assumed that she is telling stories with her own toys, or at least with ones she has collected.

Wang Liang-Yin does indeed tell stories. Her artwork is filled with stories, and this may be the main reason for her unwillingness to adopt abstraction. Her custom in every exhibition has been to present small-sized paintings of objects, medium-sized paintings, possibly landscapes or portraits, and one large-scale thematic masterpiece. This arrangement of different subject matter, canvas size, and ways of hanging paintings in the exhibition venue constructs intertextual relationships among the works, and thus serves as a way of developing narratives and scenes. Furthermore, each exhibition has a theme and related system of symbols, which creates a decoding game for the audience. Compared with previous exhibitions, The Iris of Beasts is clearly more literary, in that Wang Liang-Yin has blends in two main texts—the Bible, including several of its symbols and metaphors, such as the apple or forbidden fruit, trumpet blowing angels, the great flood, and Noah's Ark; and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's The Little Prince with the airplane, planet, rose and fox. To these two texts, which she deploys to talk about loneliness, desire, love, judgment, destruction, and redemption, the artist, deliberately or not, has added herself and her story to the exhibition. But what story is that?

When visiting the exhibition, stand in front of her 1.8 meter high and 4 meter long work titled Angels, Apples, Beasts and take note of the flood blotting out the sky. It is strange that the various pairs of beasts have not boarded the ark, but are floating or submerged in the vast flood waters. And at the center of the painting, she depicted several floating eyeballs and their delicate irises. Allegorical or prophetic painting is full of details, some of which are recognizable, such that their effects oscillated between consciousness and unconsciousness, realism and surrealism, or reality and imagination. The deconstruction, altering, and rewriting of a text have opened the boundaries of reading and led to different interpretations, and in her case, perhaps these interpretations are the result of Wang Liang-Yin's insistence on using paradoxes and divergences as her creative strategies.

Wang has been not only in Taiwan but also overseas for exhibitions such as New York, Germany, UK, Japan, Jakarta, Korea, and China. She had solo exhibitions Happy Birthday, My Dear at Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Taipei in 2014, The End of the Rainbow at Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts, Taipei in 2018. Wang's artworks are collected by National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Art Bank Taiwan, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Long Yen Foundation, Taipei National University of the Arts, Taichung County Seaport Art Center, and Sunpride Foundation, and are not only selected by Kaohsiung Award but also won the first prize of NewPerspective Art in Taiwan Dimensional Creation Series, Long Yen Foundation Creative Arts Award, Chang Hsing Lung Award and so on.

|

Wang Liang-Yin |

mpefm

TAIWAN art press release

Opening hours:

Tuesday-Saturday 11:00 - 19:00 Closed on Sunday and Monday

Opening hours:

Tuesday-Saturday 11:00 - 19:00 Closed on Sunday and Monday

QR of this press release

in your phone, tablet