"WHAT THE DAY HIDES, THE NIGHT SHOWS"

Lionel Estève

PERROTIN

TOKYO 1F, 6-6-9 ROPPONGI, MINATO-KU, TOKYO 106-0032TEL : +81 3 6721 0687 FAX : +81 3 6721 0687 e-mail:

Multiple location : Shanghai New York Paris(3) Hong Kong Tokyo Seoul

October 28 > December 28, 2022

©Estève, ADAGP Paris, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin

Perrotin Tokyo is pleased to announce What the Day Hides, The

Night Shows — the first solo exhibition in Japan by Belgian artist

Lionel Estève. The exhibition presents two types of works - drawings

on fabrics and sculptures made of stone - and explores the notions

of landscape and pareidolia. The following is an essay authored by

curator Akiko Miki on the occasion of this exhibition.

The visual arts—encompassing sculptures, paintings, and installations— tend to invite a wide myriad of interpretation through the filter of words. On occasion, however, we encounter work that almost seems to defy or even reject description. To me, Lionel Estève’s work is a prime example. Of course, this by no means implies that there is nothing to say about his work. Rather, his decisively modest and sometimes fragile creations aspire toward something that cannot be expressed in words, making me feel that any attempt at critique or interpretation may strip away the sense of pure curiosity and surprise that forms the core of his work, as well as inhibit the numerous potential discoveries thereon. The exhibition spaces Estève creates are often reminiscent of natural history museums, laboratories, or showrooms. However, the materials used in his work largely consist of prosaic objects that typically receive little attention, whether natural materials like stones, sand, shells, and tree leaves collected from the seaside and riverbeds, or colorful plastics, ropes, beads, and sequins. Many are reused materials and reclaimed scrap. Estève’s approach is extremely low-tech, mainly entailing manual work such as sewing, tying, pasting, and collage-like assemblage. Moreover, his production processes eschew specialized techniques in favor of a more accessible style that rather resembles handicrafts, often imbued with a sense of childlike play. In fact, a large portion of the artist’s oeuvre derives from his personal memories of moments spent with children and his travels around the world. For instance, during a stay in Brittany, France, he learned how to tie nets from a local fisherman and later applied the skill in his netted balloon series. He is also known for an outdoor project in a park, where he accented a tree’s foliage with literal gold leaf. As such, with just a subtle touch, the artist transforms casual, everyday materials into disparate and remarkable objects, creating unexpected landscapes.

Another characteristic of Estève’s work is the incorporation of movement and coincidence, as if the artwork itself were alive. In his kinetic sculptures made with numerous strings of mobiles, beads, and rings that swirl; feathers and curtains that sway slightly with the movement of air; and leaves that fall from trees to create various landscapes with the passage of time and seasons, we can see the artist’s interest in ever-changing forms and images in his work.

Estève’s purview, which is both figurative and abstract, lies at the intersection between fine art, popular art, and folk art. His work emphasizes and visualizes preexisting forms found in our surroundings and in nature, and explores new possibilities created by combining and relating differing elements such as the environment, space, material, color, and texture. Upon encountering his work, viewers are prompted to expand their imagination and perspective, often involving physicality, and are confronted with the question: How do you see it?

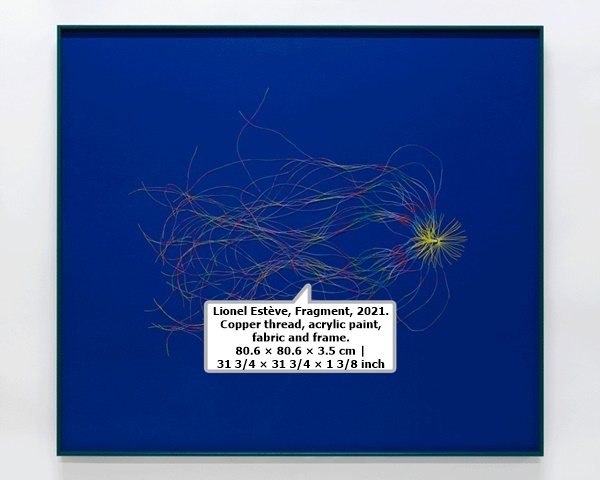

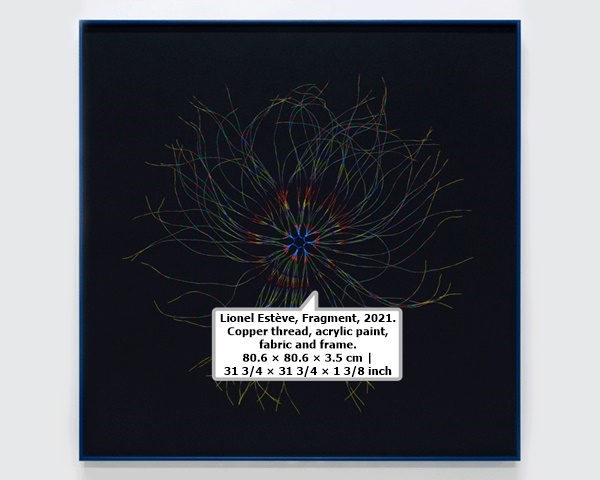

This first solo exhibition of Estève’s work in Tokyo demonstrates the artist’s employment of familiar materials—stones collected in nature and copper filaments presumably found in his studio—with the extremely simple and direct gestures that are his métier. If the multiple firework-esque images displayed on the gallery wall are fragments of the starry sky, perhaps the combination of large and small stones arranged on the floor symbolize the earth and the people living on it. The cairns, or piled stones, evoke an offering to the gods of nature and remind us of primitive nature beliefs, prototypes of craftsmanship, and the cycles of nature.

Estève’s creations are consistently inspired by nature and informed by his endeavor to discover and learn something from the natural world. This stance often opens up broader observations of contemporary society. Consider, for instance, the Chemical Landscape series (2019), in which the artist combined materials like beads and plexiglass to depict landscapes he’d visited around the world (such as Brazil and India). Or his installation at the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art (2012), where stones placed on the floor were marked with apparent traces of a flooded water-level. Both are reminders of the increasingly disastrous floods and other environmental threats caused by excessive industrialization and the chemical deluge of the modern age.

Intriguingly, while Estève’s works underscore contemporary environmental and social issues, they also always offer clues for change and positive shifts in perspective that point to renewal and hope.1 For instance, young plant buds can be seen sprouting, as a sign of life, amid the artificial and unnaturally colorful vistas of Chemical Landscape, and the vestiges of flood damage are transformed into poetic and beautiful scenery.

Inevitably, the exhibition recalls experiences such as the pandemic lockdowns that have had a significant impact on our lives on a global scale over the past few years. When mobility is restricted, how do we connect with distant objects and worlds? How will we interact with and live in our surroundings in the future? In response to these questions, Estève’s positive shift in mindset recalls the wisdom of ancient peoples, and suggests exploring the vast universe through tiny fragments as well as the richness of infinity through the use of simple, familiar materials and handwork.

Pareidolia, the theme of this exhibition, refers to a psychological phenomenon in which our minds perceive patterns and forms where they do not actually exist. The term describes the experience of seeing a rabbit in the moon, the face of a folkloric monster in the clouds, or an animal in a stain on a wall. Along with hierophany (a manifestation of the sacred) and apophenia (the perception of seeing regularity and connection in the information around us), pareidolia is said to have played a role in past societies by bringing order to chaos and making sense of the world.2 These are not mere sensory illusions, but rather the projection of order by the viewer’s perceptions and memories. Here, too, we can see that Estève’s interest lies in the expansion and potential of the human “seeing eye” in a broader sense.

In today’s chaotic world, faced as it is with war, pandemic, and natural disaster, many have pointed out the importance of breaking away from anthropocentrism—to see ourselves as a part of the surrounding environment, to make more direct contact with the world, to transcend preconceptions rather than rely only on logic and scientific laws, and further nurture the multiple perspectives and capacity for imagination humans have developed over the centuries.

Estève’s creations, though very minimal and modest, are intertwined with the fundamental aspects of life, the symbiotic and creative relationship between nature and humans, the possibility of emergence3 that creates new order out of the accumulation and organization of miscellaneous materials, and expressing the complex simply (and vice versa). In this sense, Estève’s work is a timely reminder of the forgotten origins of sensitivity and wisdom, imbued with subtle hints for how we might live in a more hopeful future.

1 Estève mentions this point in a video for an exhibition at Perrotin Paris in 2019.

2 For more on pareidolia, see Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Pareidolia (accessed: May 24, 2022)

3 Emergence is a concept used to describe phenomena in a wide range of disciplines, including biology, physics, philosophy, psychology, organizational theory, and information engineering

The visual arts—encompassing sculptures, paintings, and installations— tend to invite a wide myriad of interpretation through the filter of words. On occasion, however, we encounter work that almost seems to defy or even reject description. To me, Lionel Estève’s work is a prime example. Of course, this by no means implies that there is nothing to say about his work. Rather, his decisively modest and sometimes fragile creations aspire toward something that cannot be expressed in words, making me feel that any attempt at critique or interpretation may strip away the sense of pure curiosity and surprise that forms the core of his work, as well as inhibit the numerous potential discoveries thereon. The exhibition spaces Estève creates are often reminiscent of natural history museums, laboratories, or showrooms. However, the materials used in his work largely consist of prosaic objects that typically receive little attention, whether natural materials like stones, sand, shells, and tree leaves collected from the seaside and riverbeds, or colorful plastics, ropes, beads, and sequins. Many are reused materials and reclaimed scrap. Estève’s approach is extremely low-tech, mainly entailing manual work such as sewing, tying, pasting, and collage-like assemblage. Moreover, his production processes eschew specialized techniques in favor of a more accessible style that rather resembles handicrafts, often imbued with a sense of childlike play. In fact, a large portion of the artist’s oeuvre derives from his personal memories of moments spent with children and his travels around the world. For instance, during a stay in Brittany, France, he learned how to tie nets from a local fisherman and later applied the skill in his netted balloon series. He is also known for an outdoor project in a park, where he accented a tree’s foliage with literal gold leaf. As such, with just a subtle touch, the artist transforms casual, everyday materials into disparate and remarkable objects, creating unexpected landscapes.

Another characteristic of Estève’s work is the incorporation of movement and coincidence, as if the artwork itself were alive. In his kinetic sculptures made with numerous strings of mobiles, beads, and rings that swirl; feathers and curtains that sway slightly with the movement of air; and leaves that fall from trees to create various landscapes with the passage of time and seasons, we can see the artist’s interest in ever-changing forms and images in his work.

Estève’s purview, which is both figurative and abstract, lies at the intersection between fine art, popular art, and folk art. His work emphasizes and visualizes preexisting forms found in our surroundings and in nature, and explores new possibilities created by combining and relating differing elements such as the environment, space, material, color, and texture. Upon encountering his work, viewers are prompted to expand their imagination and perspective, often involving physicality, and are confronted with the question: How do you see it?

This first solo exhibition of Estève’s work in Tokyo demonstrates the artist’s employment of familiar materials—stones collected in nature and copper filaments presumably found in his studio—with the extremely simple and direct gestures that are his métier. If the multiple firework-esque images displayed on the gallery wall are fragments of the starry sky, perhaps the combination of large and small stones arranged on the floor symbolize the earth and the people living on it. The cairns, or piled stones, evoke an offering to the gods of nature and remind us of primitive nature beliefs, prototypes of craftsmanship, and the cycles of nature.

Estève’s creations are consistently inspired by nature and informed by his endeavor to discover and learn something from the natural world. This stance often opens up broader observations of contemporary society. Consider, for instance, the Chemical Landscape series (2019), in which the artist combined materials like beads and plexiglass to depict landscapes he’d visited around the world (such as Brazil and India). Or his installation at the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art (2012), where stones placed on the floor were marked with apparent traces of a flooded water-level. Both are reminders of the increasingly disastrous floods and other environmental threats caused by excessive industrialization and the chemical deluge of the modern age.

Intriguingly, while Estève’s works underscore contemporary environmental and social issues, they also always offer clues for change and positive shifts in perspective that point to renewal and hope.1 For instance, young plant buds can be seen sprouting, as a sign of life, amid the artificial and unnaturally colorful vistas of Chemical Landscape, and the vestiges of flood damage are transformed into poetic and beautiful scenery.

Inevitably, the exhibition recalls experiences such as the pandemic lockdowns that have had a significant impact on our lives on a global scale over the past few years. When mobility is restricted, how do we connect with distant objects and worlds? How will we interact with and live in our surroundings in the future? In response to these questions, Estève’s positive shift in mindset recalls the wisdom of ancient peoples, and suggests exploring the vast universe through tiny fragments as well as the richness of infinity through the use of simple, familiar materials and handwork.

Pareidolia, the theme of this exhibition, refers to a psychological phenomenon in which our minds perceive patterns and forms where they do not actually exist. The term describes the experience of seeing a rabbit in the moon, the face of a folkloric monster in the clouds, or an animal in a stain on a wall. Along with hierophany (a manifestation of the sacred) and apophenia (the perception of seeing regularity and connection in the information around us), pareidolia is said to have played a role in past societies by bringing order to chaos and making sense of the world.2 These are not mere sensory illusions, but rather the projection of order by the viewer’s perceptions and memories. Here, too, we can see that Estève’s interest lies in the expansion and potential of the human “seeing eye” in a broader sense.

In today’s chaotic world, faced as it is with war, pandemic, and natural disaster, many have pointed out the importance of breaking away from anthropocentrism—to see ourselves as a part of the surrounding environment, to make more direct contact with the world, to transcend preconceptions rather than rely only on logic and scientific laws, and further nurture the multiple perspectives and capacity for imagination humans have developed over the centuries.

Estève’s creations, though very minimal and modest, are intertwined with the fundamental aspects of life, the symbiotic and creative relationship between nature and humans, the possibility of emergence3 that creates new order out of the accumulation and organization of miscellaneous materials, and expressing the complex simply (and vice versa). In this sense, Estève’s work is a timely reminder of the forgotten origins of sensitivity and wisdom, imbued with subtle hints for how we might live in a more hopeful future.

1 Estève mentions this point in a video for an exhibition at Perrotin Paris in 2019.

2 For more on pareidolia, see Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Pareidolia (accessed: May 24, 2022)

3 Emergence is a concept used to describe phenomena in a wide range of disciplines, including biology, physics, philosophy, psychology, organizational theory, and information engineering

| Lionel Estève | |