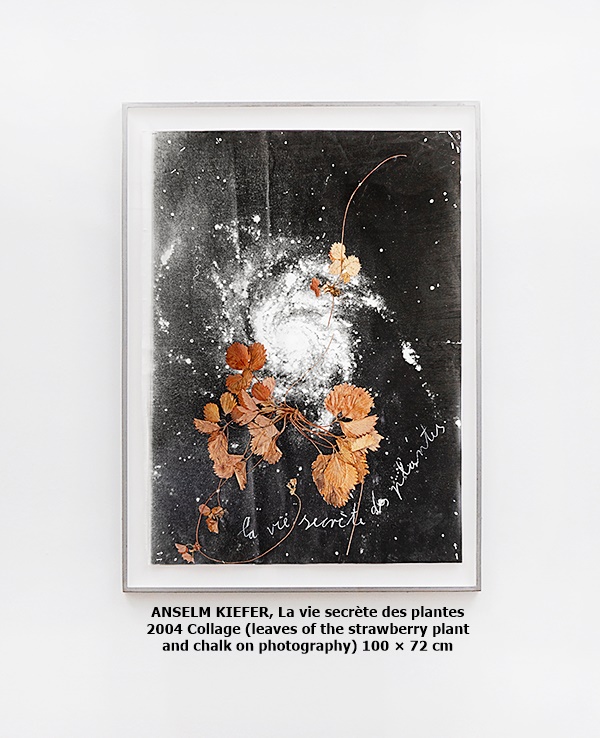

"La vie secrète des plantes"

Anselm Kiefer

BECK & EGGELING

Bilker Strasse 5 40213 Düsseldorf Germany+49.211.4 91 58 90 +49.211.4 91 58 99 e-mail:

from September, 2020

In 1617 ›Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris Metaphysica, physica atque technica Historia‹, one of the major works of the English physician, astrologer, mathematician and natural philosopher Robert Fludd (1574—1637), was published. In it, Fludd sketched out a cosmology that shows the influence of the stars on the world's events, depicting and describing in detail all the human arts and techniques of his time and explaining them by their analogy with their celestial archetypes. The Enlightenment swept most of what Fludd collected encyclopedically in the theories of the early modern era off the table as superstition and non-science—too holistically combining the approaches of philosophy, theology and the scientific knowledge of the time to be of any use to a modern, objective, mathematical natural science.

In Fludd's work there is a short sentence: »Every plant has its related star in the sky«. It is this sentence that fascinated Anselm Kiefer so much, as the artist explained in an interview with German newspaper DIE ZEIT in 2005, that he began to study Fludd's work intensively. On the one hand, this very thought seemed incredibly comforting to him. On the other hand, according to Kiefer, he also recognized in it something very modern, namely Einstein's idea of the connection between macrocosm and microcosm. Einstein had failed to find the formula of both worlds, while Fludd had already found it in a poetic way.

For Kiefer, his preoccupation with Fludd was also the starting point for a new complex of works: ›The Secret Life of Plants.‹ He borrowed this title from a book that was published by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird in 1973, in which the authors deal with the relationship between humans, plants and the universe on both a physical and psychological level in a popular scientific way (to put it sympathetically). As crude as some of the book's theses may seem, what unites the authors with Kiefer and Fludd, is the aim to explicitly relate the living or, if you will, the earthly, to the cosmic. It is a concern that has long permeated Kiefer's work, but has always shone through under the foil of overriding thematic complexes, while now, with ›The Secret Life of Plants‹ (which begins as a group of works in the late 1990s), he has begun to address the theme in concrete terms, or rather, to address the theme through holistic explanatory models.

Like other work groups before, ›The Secret Life of Plants‹ as a work complex unites a whole series of works in a wide variety of media, materials and formats, from monumental canvases to leaden sculptures and installations to smaller works, such as the collage of plant parts in photography presented here. The work was created in connection with a whole series of similar works that Kiefer published in a small but very fine artist's book in 2003 (»Anselm Kiefer: The Secret Life of Plants«, Edition Heiner Bastian, Schirmer/Mosel Verlag, Munich 2003), but was not included in the publication. In, by Kiefer's standards, an almost sparse use of material and gesture, a dried strawberry plant lies on the coarse-grained black-and-white photograph of a spiral nebula. On the right, with white chalk and in Kiefer's trademark handwriting, the title in French: that's all it takes to get to the heart of the matter. In his magical and suggestive visual language, he confidently weaves the threads of Fludd and Tompkins and Bird, creating new projection surfaces for the viewer on his screens: like the strawberry plant floating through space. Do you remember how Stanley Kubrick captured the flight of a space shuttle to a space station orbiting the earth in his opus Magnum 2001: Odyssey in Space in 5 immortal minutes of film under the 3/4 measures of Johann Strauss? A cosmic ballet. You almost wish you could hear it while beholding Kiefer's work ›An der schönen blauen Donau‹. Admittedly, the two ultimately find other images, but Kubrick also deals with the relationship of the earthly, in his case more precisely the human, to the cosmos.

And apropos film: in 1979, the aforementioned book ›The Secret Life of Plants‹ was filmed as a kind of documentation, if you will. The obscure assemblage of time-lapse photographs of botanical growth, psychedelic video sequences and involuntarily comical re-enactments of laboratory experiments by Russian researchers on plants was a big flop and would probably have been completely forgotten today if Stevie Wonder, the first musician to use the sampling technique on the album created for the film, had not been won over for the soundtrack. In the rather traditionally arranged title track he sings: "... And some believe antennas are their leaves / That spans beyond our galaxy..." Of course, there is no direct line from Stevie Wonder to Anselm Kiefer, even though the idea is somehow enjoyable, but it is interesting how both find the same images. The problem with Stevie Wonder's record is that it is a setting to music of Thompson/Bird's New Age spelling book. Of course Kiefer is not a musician, but a visual artist, and yet he is too smart anyway to be so captured. And too good. He transfers the often literary sources of his pictorial inventory into the visual, and, like a poet transforms words into semantics and syntax, by doing so creates new levels of meaning and scope for association for the viewer. Poetry for the eyes.

So what is it then that the Beatles, quoted at the beginning of this text, actually have to do with all this? Nothing! But similar to Kiefers sparseness in ›La vie secrète des plantes‹, it took John Lennon no more than three words to put it all in a nutshell: Strawberry Fields Forever.

In Fludd's work there is a short sentence: »Every plant has its related star in the sky«. It is this sentence that fascinated Anselm Kiefer so much, as the artist explained in an interview with German newspaper DIE ZEIT in 2005, that he began to study Fludd's work intensively. On the one hand, this very thought seemed incredibly comforting to him. On the other hand, according to Kiefer, he also recognized in it something very modern, namely Einstein's idea of the connection between macrocosm and microcosm. Einstein had failed to find the formula of both worlds, while Fludd had already found it in a poetic way.

For Kiefer, his preoccupation with Fludd was also the starting point for a new complex of works: ›The Secret Life of Plants.‹ He borrowed this title from a book that was published by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird in 1973, in which the authors deal with the relationship between humans, plants and the universe on both a physical and psychological level in a popular scientific way (to put it sympathetically). As crude as some of the book's theses may seem, what unites the authors with Kiefer and Fludd, is the aim to explicitly relate the living or, if you will, the earthly, to the cosmic. It is a concern that has long permeated Kiefer's work, but has always shone through under the foil of overriding thematic complexes, while now, with ›The Secret Life of Plants‹ (which begins as a group of works in the late 1990s), he has begun to address the theme in concrete terms, or rather, to address the theme through holistic explanatory models.

Like other work groups before, ›The Secret Life of Plants‹ as a work complex unites a whole series of works in a wide variety of media, materials and formats, from monumental canvases to leaden sculptures and installations to smaller works, such as the collage of plant parts in photography presented here. The work was created in connection with a whole series of similar works that Kiefer published in a small but very fine artist's book in 2003 (»Anselm Kiefer: The Secret Life of Plants«, Edition Heiner Bastian, Schirmer/Mosel Verlag, Munich 2003), but was not included in the publication. In, by Kiefer's standards, an almost sparse use of material and gesture, a dried strawberry plant lies on the coarse-grained black-and-white photograph of a spiral nebula. On the right, with white chalk and in Kiefer's trademark handwriting, the title in French: that's all it takes to get to the heart of the matter. In his magical and suggestive visual language, he confidently weaves the threads of Fludd and Tompkins and Bird, creating new projection surfaces for the viewer on his screens: like the strawberry plant floating through space. Do you remember how Stanley Kubrick captured the flight of a space shuttle to a space station orbiting the earth in his opus Magnum 2001: Odyssey in Space in 5 immortal minutes of film under the 3/4 measures of Johann Strauss? A cosmic ballet. You almost wish you could hear it while beholding Kiefer's work ›An der schönen blauen Donau‹. Admittedly, the two ultimately find other images, but Kubrick also deals with the relationship of the earthly, in his case more precisely the human, to the cosmos.

And apropos film: in 1979, the aforementioned book ›The Secret Life of Plants‹ was filmed as a kind of documentation, if you will. The obscure assemblage of time-lapse photographs of botanical growth, psychedelic video sequences and involuntarily comical re-enactments of laboratory experiments by Russian researchers on plants was a big flop and would probably have been completely forgotten today if Stevie Wonder, the first musician to use the sampling technique on the album created for the film, had not been won over for the soundtrack. In the rather traditionally arranged title track he sings: "... And some believe antennas are their leaves / That spans beyond our galaxy..." Of course, there is no direct line from Stevie Wonder to Anselm Kiefer, even though the idea is somehow enjoyable, but it is interesting how both find the same images. The problem with Stevie Wonder's record is that it is a setting to music of Thompson/Bird's New Age spelling book. Of course Kiefer is not a musician, but a visual artist, and yet he is too smart anyway to be so captured. And too good. He transfers the often literary sources of his pictorial inventory into the visual, and, like a poet transforms words into semantics and syntax, by doing so creates new levels of meaning and scope for association for the viewer. Poetry for the eyes.

So what is it then that the Beatles, quoted at the beginning of this text, actually have to do with all this? Nothing! But similar to Kiefers sparseness in ›La vie secrète des plantes‹, it took John Lennon no more than three words to put it all in a nutshell: Strawberry Fields Forever.

|

Anselm Kiefer |

mpefm GERMANY art press release

opening hours : from Tuesday to Friday between 2 and 6 pm and visits to our exhibitions are welcome by appointment. We kindly ask you to wear a face mask.

Please contact us at Tel. +49 (0)211-49 15 890 and thank you for your understanding.

QR of this press release

in your phone, tablet