Thilo Heinzmann

PERROTIN

3/F, 27 HUQIU ROAD, HUANGPU DISTRICT, SHANGHAI, 200002TEL : +86 21 6321 1234 e-mail:

Multiple location : Shanghai New York Paris(3) Hong Kong Tokyo Seoul

January 13 > March 25, 2023

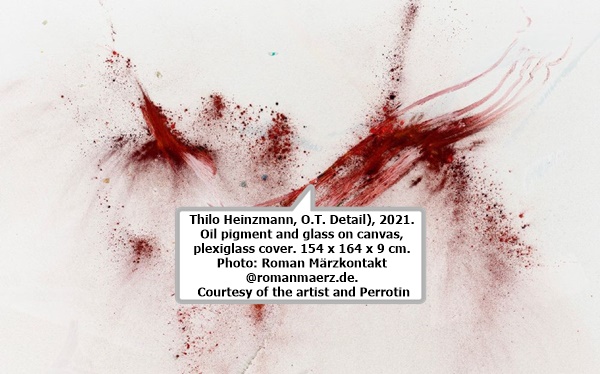

A white square picture plane above which a pigment explosion has taken

place. If we described the German artist Thilo Heinzmann’s painting in one

sentence, this is how it looks like at first sight. When Robert Rauschenberg

painted his canvas entirely white in 1951, he famously said that the white

painting was the runway for light and shadow. In a parallel comparison,

Heinzmann’s series of paintings on white canvases with dashes of pigment

could be defined as runways for bursts of color. The micro-dust of color

dancing in the air eventually lands on the canvas and sticks to its surface,

leaving us viewers wondering what it is we are seeing and how it is made ...

For the past several decades Thilo Heinzmann has been creating paintings that visually challenge the viewers and conceptually question the nature and raison d’etre of this ancient art form in our contemporary society. An unaccomplished mission in which his contemporaries have investigated and experimented in painting’s expanded fields. Heinzmann’s professor, Thomas Bayrle, contributed by reinterpreting patterned images from mass-media sources to create repeating rhythms on flat surfaces; and Martin Kippenberger, whom Heinzmann assisted during his time at the Städelschule in Frankfurt, both mocked and enchanted the medium’s resurgence.

Heinzmann’s early work Malerei (Painting,1994) was painted directly onto chipboard. By applying white paint in varying gradations of thickness, the artist recreated a soft edge that paralleled the rough-edged chipboard. Heinzmann’s work already redefines several elements of painting here: the medium, the material, and the process. The result is a serene white space containing natural rawness and artificial softness formed by artistic labor and the artist’s mind. As far as his working process is concerned, Heinzmann has combined Arte Povera’s poetic embodiment in the everyday object, post-minimalism’s highlighting of painting’s physicality, and a kind of neo- Dada action in his artistic research. From 2000 on, more materials began to appear on his paintings: polystyrene foam, epoxy resin, and crushed colored glass invite the viewers to interact with his paintings in multiple ways. When I asked how his works were made, he quoted his professor Thomas Bayrle’s advice, “A good piece of art should have at least 7% of science in it, or it will fail.” He laughed at the specification of the percentage and added, “9% works too.” A typically German humor: funny, witty, and right to the point.

So where is the science in Heinzmann’s art? The seemingly traceless chalk-white surface or background of his painting is prepared with white paint mixed with a carefully measured oil applied to the surface with brushes of various sizes. Even at this stage the artist has calculated how the adhesiveness of the paint’s sophisticated structures will affect the final painting. Then it is time to move the canvas to the garden outside his studio in Berlin and start painting. Why outside? Heinzmann’s painting is not accomplished by fixing the canvas to a static easel. The process is highly mobile. Heinzmann works with his two painter-assistants, who move the canvas to different angles and install it in various hanging systems in the garden, high and low, leaning forward and reclining backward, tilting and straightening. Heinzmann has to apply the pigments hastily according to the pre-planned composition, or all in one go. The living, adhesive quality of the white paint drying in the air leaves no room for error correction. The 18th- century Chinese master painter Zheng Banqiao left a legacy about “painting the mind image of a bamboo” when he impressed his connoisseurs by depicting a bamboo in one smooth action without looking at the bamboo forest, because he already had the image of the bamboo in his mind. Needless to say, Heinzmann’s pigment paintings have gone through such a mind-mapping before he starts painting.

There are some evident paradoxes in Heinzmann’s art that intrigue the viewers: the spontaneous formations of pigment dust caught on the canvas as opposed to the artist’s pre-designed patterns; a scientifically calculated suspension between white background and colorful pigment as opposed to an unexpected storm or sudden gust of wind that could alter everything. The element of chance, an important legacy of Dadaism to contemporary art, is transposed to the physical experiences of the viewers rather than the maker. Unlike the American post-war artists, such as Jackson Pollock and Richard Serra, whose machismo approach to art-making helped to build up their heroic personas, Heinzmann resists the temptation of the performative quality in his working process, focusing instead on establishing the authenticity of art-making in the classical way. Indeed, the act itself contains answers to his restless enquiry into the primal condition of painting.

For his Shanghai gallery exhibition,15 pigment paintings have been selected, all entitled O. T., the initials of the German “ohne Titel” (lit. without title), meaning no objective representations—or the O could stand for word “optical,” the visual effect imbued in his paintings, a pun that reveals Heinzmann’s admiration of Marcel Duchamp. The Duchampian homage is also there in the use of the box-like acrylic glass cover. During our conversation about the Shanghai exhibition, Heinzmann said that he was considering removing the glass cover so as to invite the natural dust to become part of his art. This is another Duchampian act, as dust is one of the materials in the enigmatic The Big Glass (1912–1923).

In one of the exhibited pieces, O.T. 2021, the viewers encounter a large white pictorial field, measuring 195×217×11 cm, against which clusters of black pigment are superimposed on green, red, and blue. One can feel the forceful action of applying the pigment to the canvas, by which a ripple of pigment overflowed to the side. While much action occurs in the center of the canvas, the rest is left untouched, except by splinters of colored glass.

How would a local visitor react to such a painting? The smudging dizzy effect of the scattered pigment on the white background, the explosive gesture of the pigment, the sensory traces of its movement, and the large area of whiteness left as a void—such impressions would easily remind someone with an Asian cultural background of the ink-and-paper-based traditional Chinese painting. In Chinese landscape painting the rhythm of ink absorbed by the rice paper moves poetically, soothing the mind. Although metaphysical experience is not his primary intention, Heinzmann welcomes different responses to his own reflection and action. Now that his paintings have left his studio and are here with us in Shanghai, it is his joyousness in making a painting that fascinates us viewers—and the significance of an artist’s studio, as presented by Matisse in The Red Studio, from 1911: here is me, my art, and my world. We are delighted to take a part of Heinzmann’s world and to show it to our viewers here in Shanghai.

Kaimei Olsson Wang

2022.12, Shangha

Thilo Heinzmann, born in Berlin, Germany in 1969, now lives and works in Berlin, Germany. He attended Städelschule in Frankfurt from the early 1990s in the class of Thomas Bayrle. During that time he also assisted Martin Kippenberger. A significant voice in a generation of German painters scrutinizing the medium and its history, his inventive, precise works are driven by an inquiry into what painting can be today. Using chipboard, styrofoam, nail polish, resin, pigment, fur, cotton wool, porcelain, aluminum and hessian, Heinzmann has for the last twenty-five years worked on developing new paths and an unique visual language in his practice. He is interested in the presence that each work creates, which is further enhanced by his paintings’ powerful tactile qualities. It invites the viewer to notions on some essentials: composition, surface, form, color, light, texture, and time. In 2018 he was appointed professor of painting at Universität der Künste in Berlin

For the past several decades Thilo Heinzmann has been creating paintings that visually challenge the viewers and conceptually question the nature and raison d’etre of this ancient art form in our contemporary society. An unaccomplished mission in which his contemporaries have investigated and experimented in painting’s expanded fields. Heinzmann’s professor, Thomas Bayrle, contributed by reinterpreting patterned images from mass-media sources to create repeating rhythms on flat surfaces; and Martin Kippenberger, whom Heinzmann assisted during his time at the Städelschule in Frankfurt, both mocked and enchanted the medium’s resurgence.

Heinzmann’s early work Malerei (Painting,1994) was painted directly onto chipboard. By applying white paint in varying gradations of thickness, the artist recreated a soft edge that paralleled the rough-edged chipboard. Heinzmann’s work already redefines several elements of painting here: the medium, the material, and the process. The result is a serene white space containing natural rawness and artificial softness formed by artistic labor and the artist’s mind. As far as his working process is concerned, Heinzmann has combined Arte Povera’s poetic embodiment in the everyday object, post-minimalism’s highlighting of painting’s physicality, and a kind of neo- Dada action in his artistic research. From 2000 on, more materials began to appear on his paintings: polystyrene foam, epoxy resin, and crushed colored glass invite the viewers to interact with his paintings in multiple ways. When I asked how his works were made, he quoted his professor Thomas Bayrle’s advice, “A good piece of art should have at least 7% of science in it, or it will fail.” He laughed at the specification of the percentage and added, “9% works too.” A typically German humor: funny, witty, and right to the point.

So where is the science in Heinzmann’s art? The seemingly traceless chalk-white surface or background of his painting is prepared with white paint mixed with a carefully measured oil applied to the surface with brushes of various sizes. Even at this stage the artist has calculated how the adhesiveness of the paint’s sophisticated structures will affect the final painting. Then it is time to move the canvas to the garden outside his studio in Berlin and start painting. Why outside? Heinzmann’s painting is not accomplished by fixing the canvas to a static easel. The process is highly mobile. Heinzmann works with his two painter-assistants, who move the canvas to different angles and install it in various hanging systems in the garden, high and low, leaning forward and reclining backward, tilting and straightening. Heinzmann has to apply the pigments hastily according to the pre-planned composition, or all in one go. The living, adhesive quality of the white paint drying in the air leaves no room for error correction. The 18th- century Chinese master painter Zheng Banqiao left a legacy about “painting the mind image of a bamboo” when he impressed his connoisseurs by depicting a bamboo in one smooth action without looking at the bamboo forest, because he already had the image of the bamboo in his mind. Needless to say, Heinzmann’s pigment paintings have gone through such a mind-mapping before he starts painting.

There are some evident paradoxes in Heinzmann’s art that intrigue the viewers: the spontaneous formations of pigment dust caught on the canvas as opposed to the artist’s pre-designed patterns; a scientifically calculated suspension between white background and colorful pigment as opposed to an unexpected storm or sudden gust of wind that could alter everything. The element of chance, an important legacy of Dadaism to contemporary art, is transposed to the physical experiences of the viewers rather than the maker. Unlike the American post-war artists, such as Jackson Pollock and Richard Serra, whose machismo approach to art-making helped to build up their heroic personas, Heinzmann resists the temptation of the performative quality in his working process, focusing instead on establishing the authenticity of art-making in the classical way. Indeed, the act itself contains answers to his restless enquiry into the primal condition of painting.

For his Shanghai gallery exhibition,15 pigment paintings have been selected, all entitled O. T., the initials of the German “ohne Titel” (lit. without title), meaning no objective representations—or the O could stand for word “optical,” the visual effect imbued in his paintings, a pun that reveals Heinzmann’s admiration of Marcel Duchamp. The Duchampian homage is also there in the use of the box-like acrylic glass cover. During our conversation about the Shanghai exhibition, Heinzmann said that he was considering removing the glass cover so as to invite the natural dust to become part of his art. This is another Duchampian act, as dust is one of the materials in the enigmatic The Big Glass (1912–1923).

In one of the exhibited pieces, O.T. 2021, the viewers encounter a large white pictorial field, measuring 195×217×11 cm, against which clusters of black pigment are superimposed on green, red, and blue. One can feel the forceful action of applying the pigment to the canvas, by which a ripple of pigment overflowed to the side. While much action occurs in the center of the canvas, the rest is left untouched, except by splinters of colored glass.

How would a local visitor react to such a painting? The smudging dizzy effect of the scattered pigment on the white background, the explosive gesture of the pigment, the sensory traces of its movement, and the large area of whiteness left as a void—such impressions would easily remind someone with an Asian cultural background of the ink-and-paper-based traditional Chinese painting. In Chinese landscape painting the rhythm of ink absorbed by the rice paper moves poetically, soothing the mind. Although metaphysical experience is not his primary intention, Heinzmann welcomes different responses to his own reflection and action. Now that his paintings have left his studio and are here with us in Shanghai, it is his joyousness in making a painting that fascinates us viewers—and the significance of an artist’s studio, as presented by Matisse in The Red Studio, from 1911: here is me, my art, and my world. We are delighted to take a part of Heinzmann’s world and to show it to our viewers here in Shanghai.

Kaimei Olsson Wang

2022.12, Shangha

Thilo Heinzmann, born in Berlin, Germany in 1969, now lives and works in Berlin, Germany. He attended Städelschule in Frankfurt from the early 1990s in the class of Thomas Bayrle. During that time he also assisted Martin Kippenberger. A significant voice in a generation of German painters scrutinizing the medium and its history, his inventive, precise works are driven by an inquiry into what painting can be today. Using chipboard, styrofoam, nail polish, resin, pigment, fur, cotton wool, porcelain, aluminum and hessian, Heinzmann has for the last twenty-five years worked on developing new paths and an unique visual language in his practice. He is interested in the presence that each work creates, which is further enhanced by his paintings’ powerful tactile qualities. It invites the viewer to notions on some essentials: composition, surface, form, color, light, texture, and time. In 2018 he was appointed professor of painting at Universität der Künste in Berlin

| Thilo Heinzmann | |

Opening Friday January 13, 2023