"HEALING"

Chiho Aoshima, Emi Kuraya, Takuro Kuwata, KYNE, Kasing Lung, MADSAKI, Mr., Takashi Murakami, Shin Murata, ob, Otani Workshop, Aya Takano, TENGAone, Yuji Ueda

curated by Takashi Murakami

PERROTIN

3/F, 27 HUQIU ROAD, HUANGPU DISTRICT, SHANGHAI, 200002TEL : +86 21 6321 1234 e-mail:

Multiple location : Shanghai New York Paris(3) Hong Kong Tokyo Seoul

February 5 > March 20, 2021

Perrotin Shanghai is delighted to present Healing, an exhibition devoted

to Kaikai Kiki artists: Chiho Aoshima, Emi Kuraya, Takuro Kuwata, KYNE,

Kasing Lung, MADSAKI, Mr., Takashi Murakami, Shin Murata, ob, Otani

Workshop, Aya Takano, TENGAone, and Yuji Ueda. This exhibition

comes as the last episode of the trilogy group show curated by Takashi

Murakami, following its two previous chapters last year at Perrotin Seoul

and Perrotin Matignon in Paris.

Healing explores the multifaceted and eccentric universe that is Takashi Murakami’s Superflat and the far-reaching and deep influence of Japanese ceramic arts in the context of Bubblewrap[1]. While in the west art is predicated on the differences between “highbrow” and “lowbrow” culture, “original” and “derivative,” “art” and “commodity,” Superflat establishes itself as an independent lineage of Japanese contemporary art that roots itself in anime and manga.

Takashi Murakami first coined the term Superflat in his examination of postwar Japanese society, where the boundary between traditional and contemporary culture was perceived to be ‘flat’. Past and present, original and derivative, high culture and low culture merge as one in Superflat, subverting the discourse of Western conventional divisions and challenging their legacy in the contemporary art landscape with an idiosyncratic Japanese sensibility.

Kaikai and Kiki, two of the most recognizable characters created by Murakami, are featured in the artist’s works in the exhibition. Part of Murakami’s iconography since 2000, these are two characters that take influences from Japanese manga, cartoons from the US, and to ever evolving popular culture. Kaikai and Kiki have their names — borrowed from an expression “kaikaikiki” (“strange and mysterious”) that was originally used to describe the works by sixteenth-century master Eitoku Kano[2]— rendered in Japanese script on their ears. It follows a practice that has its roots in Japanese woodblock prints, where popular characters would be indicated by writing the names next to the figure themselves.

Kaikai, a childlike character in a rabbit costume, and Kiki, an impish figure with three eyes and two dangling fangs, are normally shown together. They have at times been described by Murakami as representing good and evil. In both cases, though, this is not a metaphysical fight between moral polar opposite: it is something much closer to home, and each of us — playfulness that can turn into naughtiness without losing its innocence; mischievousness that can be slightly disturbing, but is overwhelmed by its own kawaii-ness.

A monumental, ambitious, 15-meter-long acrylic painting mounted on an aluminum frame by Murakami is also included in the exhibition. The artist embraced the beaming, overjoyed flora and adopted it as one of his emblems when preparing for entrance exams for the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music[3], and after spending nearly a decade teaching prep-school students how to draw flowers. The inspiration behind Murakami’s flowers are derived from his early studies of Nihonga painting, where he attempted to paint flowers in the setsugetsuka tradition. Signifying peace and happiness on the outside, the floral motif yet evokes repressed, contradictory emotions experienced by the Japanese as a result of the historical traumas in the 1940s. Presented in a wide spectrum of colors, from rainbow hues to at times a darker palette, the iconic polychromatic petals surrounding smiling faces are one of his most often employed motifs in the Superflat world.

The radical affiliation and lack of distinction between post-war Japan’s fine arts and popular arts is strongly linked to otaku[4] culture. In its infantile and marginal existence, the world of otaku could be seen as similar to post-war Japanese society. This isolated world establishes one of fantasy, rooted in the need to overcome reality – a reality where otaku (as social outcasts) are excluded from mainstream society and its value systems.

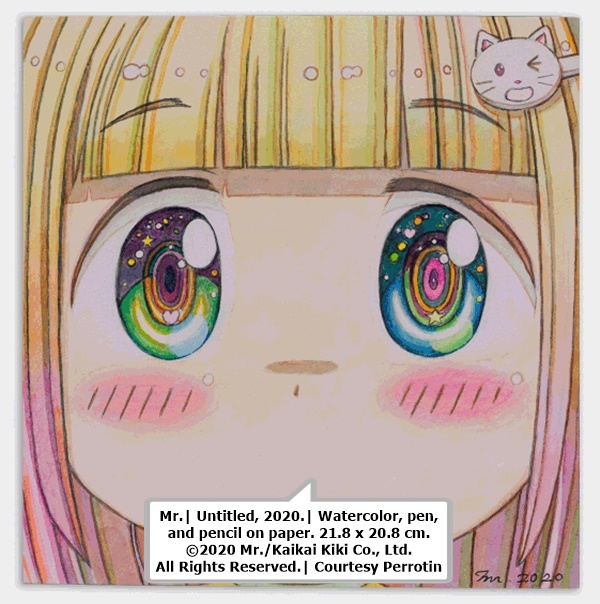

In a Superflat world, the otaku becomes the true driver of contemporary culture by externalising his inner world. Mr. built his career on anime and videogame-like renditions of everyday Japanese girls. A true otaku, and the first of his kind, Mr. singlehandedly undid the stigma of producing artworks in an anime style: “For me, [my identification with otaku] was a matter of making anime and manga into art—this has not been done historically.”

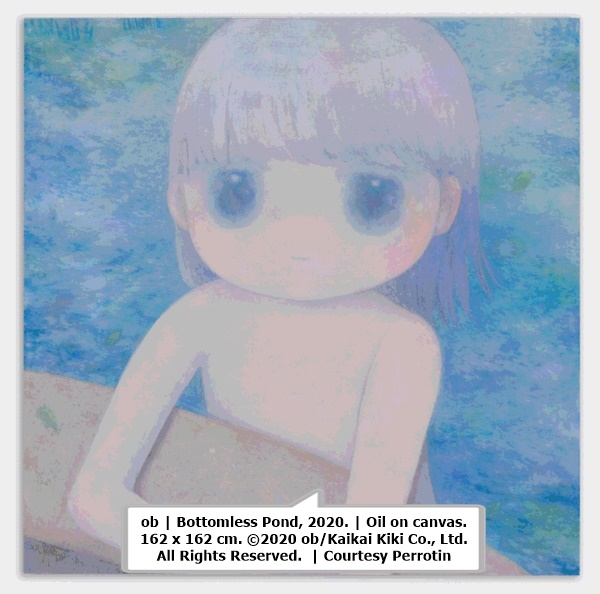

As part of the new generation of artists who grew up in an environment where video games and social media have always been part of daily life, also known as Japan’s SNS generation, Emi Kuraya and ob, explore the dreamy filter of the feminine psyche through kawaii elements: cartoonlike forms; and over-scaled heads with wide eyes and baby faces.

This intersection of reality and fantasy is an important dimension of Superflat that is perhaps best illustrated in the works of Chiho Aoshima and Aya Takano. Both artists present the viewer with fantastical worlds of a Utopian nature. Aoshima’s liminal spaces are populated by female characters who are transformed into mountains and rivers, disguised as fairies or represented as living creatures in the natural world. This breakdown of the boundaries between humans and animals or plants, and between organic creatures and inanimate objects is echoed in Aya Takano’s oeuvre. The latter’s floating figures, unphased by the restrictions of gravity, are at one with the universe, conversing with other-worldly animals and plants. There is no hierarchy in either Aoshima or Takano’s work, all cohabitate in perfect harmony, all are equal, much like Superflat itself.

Superflat focuses not only on contemporary art, but extends itself to contemporary ceramics. However, it is Bubblewrap, a term humorously coined[5] by Takashi Murakami to describe the interim period between Mono-ha and Superflat overlapping with Japan’s bubble economy, that best reflects the modern realm of ceramics. Indeed, the rise and maturation of ceramic art is juxtaposed with Japan’s Bubble Economy era. It is at this time that the “ceramics of modern life” appear. These ceramics represent a shift and new phase in the history of ceramics: their popularization. Ceramics thus become, like manga and anime, another popular art of post-war Japanese culture.

A new generation of Japanese ceramicists that Murakami dubs “radical artists”: Takuro Kuwata, Shin Murata, Otani Workshop and Yuji Ueda shed the principle of artisanal technique and adopt the posture of artists, pushing the boundary between ceramics and sculpture (or as Superflat would have it, between ‘commodity’ and ‘art’). Their unique pottery methods merge a respect for tradition and lineage with improvisation and experimentation, in a body of work informed by their love of nature and sustainable lifestyle.

The theme of alienation and/or disconnect is prevalent in the works of MADSAKI and TENGAone, although not themselves otaku. Both artists are heavily influenced by graffiti and use the medium to express the frustration and feeling of estrangement brought about by their bicultural identities. Street art is also an influence for Kasing Lung and KYNE, whose works are influenced by the economic and cultural boom of the 80’s. Raised in Europe whereby fairy tales and folklores are deeply rooted in people’s culture, Lung has developed a profound interest in the fantastical and created his very own magical realm. The anonymous female characters under KYNE creation are mostly found on the internet, from time to time, the void of emotion from the figures is exactly what the artist intends to exhibit.

Healing illustrates the undeniable importance of Superflat and Bubblewrap in the contemporary art scene, disrupting the symbolic order of Western Art History. Incessantly moving between past, present and future, while mixing high culture and popular culture indiscriminately, is a “superflat” group of works devoid of prejudice or boundaries: a truly free expression of creativity.

---------------------

[1]“After Mono-ha, the next established art movement is Superflat, but that means the interim period overlapping the years of Japan’s economic bubble has yet to be named, and I think calling it “Bubblewrap” suits it well. It especially makes sense if you incorporate the realm of ceramics.” — Takashi Murakami

[2]Kanō Eitoku (1543 –1590) was a Japanese painter who lived during the Azuchi– Momoyama period of Japanese history and one of the most prominent patriarchs of the Kanō school of Japanese painting. He was known for the blend of weirdness and refinement in his works.

[3]Now called Tokyo University of the Arts (2008).

[4]Otaku is a Japanese term for people with consuming interests, particularly in anime and manga. The otaku subculture began in the 1980s and continued to grow with the resignation of such individuals to become social outcasts and the expansion of the internet.

[5]Bubblewrap is a word play on ‘bubble economy’ and ‘bubble wrap,’ the material used to wrap and protect ceramics. Takashi Murakami is suggesting bubble wrap is reflective of the Japanese aesthetic of appreciation of fragility and honorable poverty.

Healing explores the multifaceted and eccentric universe that is Takashi Murakami’s Superflat and the far-reaching and deep influence of Japanese ceramic arts in the context of Bubblewrap[1]. While in the west art is predicated on the differences between “highbrow” and “lowbrow” culture, “original” and “derivative,” “art” and “commodity,” Superflat establishes itself as an independent lineage of Japanese contemporary art that roots itself in anime and manga.

Takashi Murakami first coined the term Superflat in his examination of postwar Japanese society, where the boundary between traditional and contemporary culture was perceived to be ‘flat’. Past and present, original and derivative, high culture and low culture merge as one in Superflat, subverting the discourse of Western conventional divisions and challenging their legacy in the contemporary art landscape with an idiosyncratic Japanese sensibility.

Kaikai and Kiki, two of the most recognizable characters created by Murakami, are featured in the artist’s works in the exhibition. Part of Murakami’s iconography since 2000, these are two characters that take influences from Japanese manga, cartoons from the US, and to ever evolving popular culture. Kaikai and Kiki have their names — borrowed from an expression “kaikaikiki” (“strange and mysterious”) that was originally used to describe the works by sixteenth-century master Eitoku Kano[2]— rendered in Japanese script on their ears. It follows a practice that has its roots in Japanese woodblock prints, where popular characters would be indicated by writing the names next to the figure themselves.

Kaikai, a childlike character in a rabbit costume, and Kiki, an impish figure with three eyes and two dangling fangs, are normally shown together. They have at times been described by Murakami as representing good and evil. In both cases, though, this is not a metaphysical fight between moral polar opposite: it is something much closer to home, and each of us — playfulness that can turn into naughtiness without losing its innocence; mischievousness that can be slightly disturbing, but is overwhelmed by its own kawaii-ness.

A monumental, ambitious, 15-meter-long acrylic painting mounted on an aluminum frame by Murakami is also included in the exhibition. The artist embraced the beaming, overjoyed flora and adopted it as one of his emblems when preparing for entrance exams for the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music[3], and after spending nearly a decade teaching prep-school students how to draw flowers. The inspiration behind Murakami’s flowers are derived from his early studies of Nihonga painting, where he attempted to paint flowers in the setsugetsuka tradition. Signifying peace and happiness on the outside, the floral motif yet evokes repressed, contradictory emotions experienced by the Japanese as a result of the historical traumas in the 1940s. Presented in a wide spectrum of colors, from rainbow hues to at times a darker palette, the iconic polychromatic petals surrounding smiling faces are one of his most often employed motifs in the Superflat world.

The radical affiliation and lack of distinction between post-war Japan’s fine arts and popular arts is strongly linked to otaku[4] culture. In its infantile and marginal existence, the world of otaku could be seen as similar to post-war Japanese society. This isolated world establishes one of fantasy, rooted in the need to overcome reality – a reality where otaku (as social outcasts) are excluded from mainstream society and its value systems.

In a Superflat world, the otaku becomes the true driver of contemporary culture by externalising his inner world. Mr. built his career on anime and videogame-like renditions of everyday Japanese girls. A true otaku, and the first of his kind, Mr. singlehandedly undid the stigma of producing artworks in an anime style: “For me, [my identification with otaku] was a matter of making anime and manga into art—this has not been done historically.”

As part of the new generation of artists who grew up in an environment where video games and social media have always been part of daily life, also known as Japan’s SNS generation, Emi Kuraya and ob, explore the dreamy filter of the feminine psyche through kawaii elements: cartoonlike forms; and over-scaled heads with wide eyes and baby faces.

This intersection of reality and fantasy is an important dimension of Superflat that is perhaps best illustrated in the works of Chiho Aoshima and Aya Takano. Both artists present the viewer with fantastical worlds of a Utopian nature. Aoshima’s liminal spaces are populated by female characters who are transformed into mountains and rivers, disguised as fairies or represented as living creatures in the natural world. This breakdown of the boundaries between humans and animals or plants, and between organic creatures and inanimate objects is echoed in Aya Takano’s oeuvre. The latter’s floating figures, unphased by the restrictions of gravity, are at one with the universe, conversing with other-worldly animals and plants. There is no hierarchy in either Aoshima or Takano’s work, all cohabitate in perfect harmony, all are equal, much like Superflat itself.

Superflat focuses not only on contemporary art, but extends itself to contemporary ceramics. However, it is Bubblewrap, a term humorously coined[5] by Takashi Murakami to describe the interim period between Mono-ha and Superflat overlapping with Japan’s bubble economy, that best reflects the modern realm of ceramics. Indeed, the rise and maturation of ceramic art is juxtaposed with Japan’s Bubble Economy era. It is at this time that the “ceramics of modern life” appear. These ceramics represent a shift and new phase in the history of ceramics: their popularization. Ceramics thus become, like manga and anime, another popular art of post-war Japanese culture.

A new generation of Japanese ceramicists that Murakami dubs “radical artists”: Takuro Kuwata, Shin Murata, Otani Workshop and Yuji Ueda shed the principle of artisanal technique and adopt the posture of artists, pushing the boundary between ceramics and sculpture (or as Superflat would have it, between ‘commodity’ and ‘art’). Their unique pottery methods merge a respect for tradition and lineage with improvisation and experimentation, in a body of work informed by their love of nature and sustainable lifestyle.

The theme of alienation and/or disconnect is prevalent in the works of MADSAKI and TENGAone, although not themselves otaku. Both artists are heavily influenced by graffiti and use the medium to express the frustration and feeling of estrangement brought about by their bicultural identities. Street art is also an influence for Kasing Lung and KYNE, whose works are influenced by the economic and cultural boom of the 80’s. Raised in Europe whereby fairy tales and folklores are deeply rooted in people’s culture, Lung has developed a profound interest in the fantastical and created his very own magical realm. The anonymous female characters under KYNE creation are mostly found on the internet, from time to time, the void of emotion from the figures is exactly what the artist intends to exhibit.

Healing illustrates the undeniable importance of Superflat and Bubblewrap in the contemporary art scene, disrupting the symbolic order of Western Art History. Incessantly moving between past, present and future, while mixing high culture and popular culture indiscriminately, is a “superflat” group of works devoid of prejudice or boundaries: a truly free expression of creativity.

---------------------

[1]“After Mono-ha, the next established art movement is Superflat, but that means the interim period overlapping the years of Japan’s economic bubble has yet to be named, and I think calling it “Bubblewrap” suits it well. It especially makes sense if you incorporate the realm of ceramics.” — Takashi Murakami

[2]Kanō Eitoku (1543 –1590) was a Japanese painter who lived during the Azuchi– Momoyama period of Japanese history and one of the most prominent patriarchs of the Kanō school of Japanese painting. He was known for the blend of weirdness and refinement in his works.

[3]Now called Tokyo University of the Arts (2008).

[4]Otaku is a Japanese term for people with consuming interests, particularly in anime and manga. The otaku subculture began in the 1980s and continued to grow with the resignation of such individuals to become social outcasts and the expansion of the internet.

[5]Bubblewrap is a word play on ‘bubble economy’ and ‘bubble wrap,’ the material used to wrap and protect ceramics. Takashi Murakami is suggesting bubble wrap is reflective of the Japanese aesthetic of appreciation of fragility and honorable poverty.

| Chiho Aoshima |

| Emi Kuraya |

| Takuro Kuwata |

| KYNE |

| Kasing Lung |

| MADSAKI |

| Mr. |

| Takashi Murakami |

| Shin Murata |

| ob |

| Otani Workshop |

| Aya Takano |

| TENGAone |

| Yuji Ueda |

Opening reception :

Friday February 5, 2021

mpefm

CHINA art press release

Opening Hours:

TUESDAY - SATURDAY, 10AM - 7PM

Opening Hours:

TUESDAY - SATURDAY, 10AM - 7PM

QR of this press release

in your phone, tablet